1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

42

43

44

45

46

47

48

49

50

51

52

53

54

55

56

57

58

59

60

61

62

63

64

65

66

67

68

69

70

71

72

73

74

75

76

77

78

79

80

81

82

83

84

85

86

87

88

89

90

91

92

93

94

95

96

97

98

99

100

101

102

103

104

105

106

107

108

109

110

111

112

113

114

115

116

117

118

119

120

121

122

|

---

# Gyrotropic Media

---

In this example, we will perform simulations with gyrotropic media. See [Materials](../Materials.md#gyrotropic-media) for more information on how gyrotropy is supported.

[TOC]

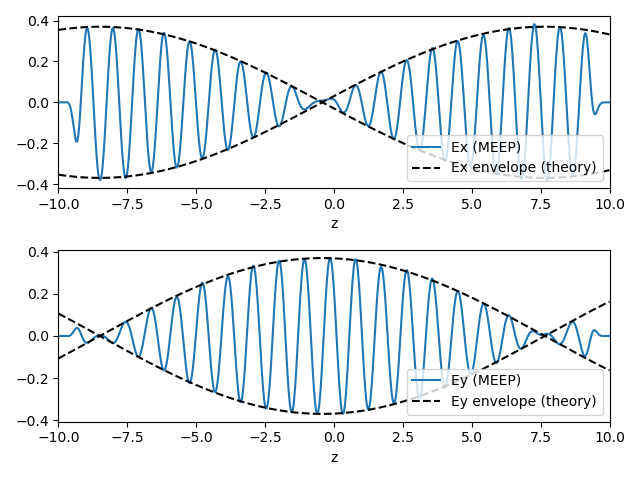

### Faraday Rotation

Consider a uniform gyroelectric medium with bias vector $\mathbf{b} = b \hat{z}$. In the frequency domain, the *x* and *y* components of the dielectric tensor have the form

$$\epsilon = \begin{bmatrix}\epsilon_\perp & -i\eta \\ i\eta & \epsilon_\perp \end{bmatrix}$$

The skew-symmetric off-diagonal components give rise to [Faraday rotation](https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Faraday_effect): when a plane wave linearly polarized along *x* is launched along the gyrotropy axis *z*, the polarization vector will precess around the gyrotropy axis as the wave propagates. This is the principle behind [Faraday rotators](https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Faraday_rotator), devices that act as one-way valves for light.

A plane wave undergoing Faraday rotation can be described by the complex ansatz

$$\begin{bmatrix}E_x \\ E_y\end{bmatrix} = E_0 \begin{bmatrix}\cos(\kappa_c z) \\ \sin(\kappa_c z)\end{bmatrix} e^{i(kz-\omega t)}$$

where $\kappa_c$ is the Faraday rotation (in radians) per unit of propagation distance. Substituting this into the frequency domain Maxwell's equations, with the above dielectric tensor, yields

$$|\kappa_c| = \omega \sqrt{\frac{\mu}{2} \, \left(\epsilon_\perp - \sqrt{\epsilon_\perp^2 - \eta^2}\right)}$$

We model this phenomenon in the simulation script [faraday-rotation.py](https://github.com/NanoComp/meep/blob/master/python/examples/faraday-rotation.py). First, we define a gyroelectric material:

```python

import meep as mp

## Parameters for a gyrotropic Lorentzian medium

epsn = 1.5 # background permittivity

f0 = 1.0 # natural frequency

gamma = 1e-6 # damping rate

sn = 0.1 # sigma parameter

b0 = 0.15 # magnitude of bias vector

susc = [mp.GyrotropicLorentzianSusceptibility(frequency=f0, gamma=gamma, sigma=sn,

bias=mp.Vector3(0, 0, b0))]

mat = mp.Medium(epsilon=epsn, mu=1, E_susceptibilities=susc)

```

The `GyrotropicLorentzianSusceptibility` object has a `bias` argument that takes a `Vector3` specifying the gyrotropy vector. In this case, the vector points along *z*, and its magnitude (which specifies the precession frequency) is determined by the variable `b0`. The other arguments play the same role as in an ordinary (non-gyrotropic) [Lorentzian susceptibility](Material_Dispersion.md).

Next, we set up and run the Meep simulation.

```python

tmax = 100

L = 20.0

cell = mp.Vector3(0, 0, L)

fsrc, src_z = 0.8, -8.5

pml_layers = [mp.PML(thickness=1.0, direction=mp.Z)]

sources = [mp.Source(mp.ContinuousSource(frequency=fsrc),

component=mp.Ex, center=mp.Vector3(0, 0, src_z))]

sim = mp.Simulation(cell_size=cell, geometry=[], sources=sources,

boundary_layers=pml_layers,

default_material=mat, resolution=50)

sim.run(until=tmax)

```

The simulation cell is one pixel wide in the *x* and *y* directions, with periodic boundary conditions. [PMLs](../Perfectly_Matched_Layer.md) are placed in the *z* direction. A `ContinuousSource` emits a wave whose electric field is initially polarized along *x*. We then plot the *x* and *y* components of the electric field versus *z*:

```python

import numpy as np

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

ex_data = sim.get_efield_x().real

ey_data = sim.get_efield_y().real

z = np.linspace(-L/2, L/2, len(ex_data))

plt.figure(1)

plt.plot(z, ex_data, label='Ex')

plt.plot(z, ey_data, label='Ey')

plt.xlim(-L/2, L/2)

plt.xlabel('z')

plt.legend()

plt.show()

```

<center>

</center>

We see that the wave indeed rotates in the *x*-*y* plane as it travels.

Moreover, we can compare the Faraday rotation rate in these simulation results to theoretical predictions. In the [gyrotropic Lorentzian model](../Materials.md#gyrotropic-media), the ε tensor components are given by

$$\epsilon_\perp = \epsilon_\infty + \frac{\omega_n^2 \Delta_n}{\Delta_n^2 - \omega^2 b^2}\,\sigma_n(\mathbf{x}),\;\;\; \eta = \frac{\omega_n^2 \omega b}{\Delta_n^2 - \omega^2 b^2}\,\sigma_n(\mathbf{x}), \;\;\;\Delta_n \equiv \omega_n^2 - \omega^2 - i\omega\gamma_n$$

From these expressions, we can calculate the rotation rate $\kappa_c$ at the operating frequency, and hence find the $\mathbf{E}_x$ and $\mathbf{E}_y$ field envelopes for the complex ansatz given at the top of this section.

```python

dfsq = (f0**2 - 1j*fsrc*gamma - fsrc**2)

eperp = epsn + sn * f0**2 * dfsq / (dfsq**2 - (fsrc*b0)**2)

eta = sn * f0**2 * fsrc * b0 / (dfsq**2 - (fsrc*b0)**2)

k_gyro = 2*np.pi*fsrc * np.sqrt(0.5*(eperp - np.sqrt(eperp**2 - eta**2)))

Ex_theory = 0.37 * np.cos(k_gyro * (z - src_z)).real

Ey_theory = 0.37 * np.sin(k_gyro * (z - src_z)).real

plt.figure(2)

plt.subplot(2,1,1)

plt.plot(z, ex_data, label='Ex (MEEP)')

plt.plot(z, Ex_theory, 'k--')

plt.plot(z, -Ex_theory, 'k--', label='Ex envelope (theory)')

plt.xlim(-L/2, L/2); plt.xlabel('z')

plt.legend(loc='lower right')

plt.subplot(2,1,2)

plt.plot(z, ey_data, label='Ey (MEEP)')

plt.plot(z, Ey_theory, 'k--')

plt.plot(z, -Ey_theory, 'k--', label='Ey envelope (theory)')

plt.xlim(-L/2, L/2); plt.xlabel('z')

plt.legend(loc='lower right')

plt.tight_layout()

plt.show()

```

As shown in the figure below, the results are in excellent agreement:

|