1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

42

43

44

45

46

47

48

49

50

51

52

53

54

55

56

57

58

59

60

61

62

63

64

65

66

67

68

69

70

71

72

73

74

75

76

77

78

79

80

81

82

83

84

85

86

87

88

89

90

91

92

93

94

95

96

97

98

99

100

101

102

103

104

105

106

107

108

109

110

111

112

113

114

115

116

117

118

119

120

121

122

123

124

125

126

127

128

129

130

131

132

133

134

135

136

137

138

139

140

141

142

143

144

145

146

147

148

149

150

151

152

153

154

155

156

157

158

159

160

161

162

163

164

165

166

167

168

169

170

171

172

173

174

175

176

177

178

179

180

181

182

183

184

185

186

187

188

189

190

191

192

193

194

195

196

197

198

199

200

201

202

203

204

205

206

207

208

209

210

211

212

213

214

215

216

217

218

219

220

221

222

223

224

225

226

227

228

229

230

231

232

233

234

235

236

237

238

239

240

241

242

243

244

245

246

247

248

249

250

251

252

253

254

255

256

257

258

259

260

261

262

263

264

265

266

267

268

269

270

271

272

273

274

275

276

277

278

279

280

281

282

283

284

285

286

287

288

289

290

291

292

293

294

295

296

297

298

299

300

301

302

303

304

305

306

307

308

309

310

311

312

313

314

315

316

317

318

319

320

321

322

323

324

325

326

327

328

329

330

331

332

333

334

335

336

337

338

339

340

341

342

343

344

345

346

347

348

349

350

351

352

353

354

355

356

357

358

359

360

361

362

363

364

365

366

367

368

369

370

371

372

373

374

375

376

377

378

379

380

381

382

383

384

385

386

387

388

389

390

391

392

393

394

395

396

397

398

399

400

401

402

403

404

405

406

407

408

409

410

411

412

413

414

415

416

417

418

419

420

421

422

423

424

425

426

427

428

429

430

431

432

433

434

435

436

437

438

439

440

441

442

443

444

445

446

447

448

449

450

451

452

453

454

455

456

457

458

459

460

461

462

463

464

465

466

467

468

469

470

471

472

473

474

475

476

477

478

479

480

481

482

483

484

485

486

487

488

489

490

491

492

493

494

495

496

497

498

499

500

501

502

503

504

505

506

507

508

509

510

511

512

513

514

515

516

517

518

519

520

521

522

523

524

525

526

527

528

529

530

531

532

533

534

535

536

537

538

539

540

541

542

543

544

545

546

547

548

549

550

551

552

553

554

555

556

557

558

559

560

561

562

563

564

565

566

567

568

569

570

571

572

573

574

575

576

577

578

579

580

581

582

583

584

585

586

587

588

589

590

591

592

593

594

595

596

597

598

599

600

601

602

603

604

605

606

607

608

609

610

611

612

613

614

615

616

617

618

619

620

621

622

623

624

625

626

627

628

629

630

631

632

633

634

635

636

637

638

639

640

641

642

643

644

645

646

647

648

649

650

651

652

653

654

655

656

657

658

659

660

661

662

663

664

665

666

667

668

669

670

671

672

673

674

675

676

677

678

679

680

681

682

683

684

685

686

687

688

689

690

691

692

693

694

695

696

697

698

699

700

701

702

703

704

705

706

707

708

709

710

711

712

713

714

715

716

717

718

719

720

721

722

723

724

725

726

727

728

729

730

731

732

733

734

735

736

737

738

739

740

741

742

743

744

745

746

747

748

749

750

751

752

753

754

755

756

757

758

759

760

761

762

763

764

765

766

767

768

769

770

771

772

773

774

775

776

777

778

779

780

781

782

783

784

785

786

787

788

789

790

791

792

793

794

795

796

797

798

799

800

801

802

803

804

805

806

807

808

809

810

811

812

813

814

815

816

817

818

819

820

821

822

823

824

825

826

827

828

829

830

831

832

833

834

835

836

837

838

839

840

841

842

843

844

845

846

847

848

849

850

851

852

853

854

855

856

857

858

859

860

861

862

863

864

865

866

867

868

869

870

871

872

873

874

875

876

877

878

879

880

881

882

883

884

885

886

887

888

889

890

891

892

893

894

895

896

897

898

899

900

901

902

903

904

905

906

907

908

909

910

911

912

913

914

915

916

917

918

919

920

921

922

923

924

925

926

927

928

929

930

931

932

933

934

935

936

937

938

939

940

941

942

943

944

945

946

947

948

949

950

951

952

953

954

955

956

957

958

959

960

961

962

963

964

965

966

967

968

969

970

971

972

973

974

975

976

977

978

979

980

981

982

983

984

985

986

987

988

989

990

991

992

993

994

995

996

997

998

999

1000

1001

1002

1003

1004

1005

1006

1007

1008

1009

1010

1011

1012

1013

1014

1015

1016

1017

1018

1019

1020

1021

1022

1023

1024

1025

1026

1027

1028

1029

1030

1031

1032

1033

1034

1035

1036

1037

1038

1039

1040

1041

1042

1043

1044

1045

1046

1047

1048

1049

1050

1051

1052

1053

1054

1055

1056

1057

1058

1059

1060

1061

1062

1063

1064

1065

1066

1067

1068

1069

1070

1071

1072

1073

1074

1075

1076

1077

1078

1079

1080

1081

1082

1083

1084

1085

1086

1087

1088

1089

1090

1091

1092

1093

1094

1095

1096

1097

1098

1099

1100

1101

1102

|

---

# Mode Decomposition

---

This tutorial demonstrates the [mode-decomposition](../Mode_Decomposition.md) feature which is used to decompose a given mode profile via the Fourier-transformed fields into a superposition of harmonic basis modes. Examples are provided for two kinds of modes in lossless, dielectric media: (1) localized (i.e., guided) and (2) non-localized (i.e., radiative planewave).

[TOC]

Reflectance of a Waveguide Taper

--------------------------------

This example involves computing the reflectance of the fundamental mode of a linear waveguide taper. The structure and the simulation parameters are shown in the schematic below. We will verify that computing the reflectance, the fraction of the incident power which is reflected, using two different methods produces nearly identical results: (1) mode decomposition and (2) [Poynting flux](../Introduction.md#transmittancereflectance-spectra). Also, we will demonstrate that the scaling of the reflectance with the taper length is quadratic, consistent with analytical results from [Optics Express, Vol. 16, pp. 11376-92 (2008)](http://www.opticsinfobase.org/abstract.cfm?URI=oe-16-15-11376).

The structure, which can be viewed as a [two-port network](https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Two-port_network), consists of a single-mode waveguide of width 1 μm (`w1`) at a wavelength of 6.67 μm and coupled to a second waveguide of width 2 μm (`w2`) via a linearly-sloped taper of variable length `Lt`. The material is silicon with $\varepsilon=12$. The taper geometry is defined using a single [`Prism`](../Python_User_Interface.md#prism) object with eight vertices. PML absorbing boundaries surround the entire cell. An eigenmode current source with $E_z$ (or $\mathcal{S}$) polarization is used to launch the fundamental mode. The dispersion relation (or "band diagram") of the single-mode waveguide is shown in [Tutorial/Eigenmode Source](Eigenmode_Source.md). There is an eigenmode-expansion monitor placed at the midpoint of the first waveguide. This is a line monitor which extends beyond the waveguide in order to span the entire mode profile including its evanescent tails. The Fourier-transformed fields along this line monitor are used to compute the basis coefficients of the harmonic modes. These are computed separately via the eigenmode solver [MPB](https://mpb.readthedocs.io/en/latest/). This is described in [Mode Decomposition](../Mode_Decomposition.md) where it is also shown that the squared magnitude of the mode coefficient is equivalent to the power (Poynting flux) in the given eigenmode. The ratio of the complex mode coefficients can be used to compute the [S parameters](https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Scattering_parameters). In this example, we are computing $|S_{11}|^2$ which is the reflectance (shown in the line prefixed by "refl:,"). Another line monitor could have been placed in the second waveguide to compute the transmittance or $|S_{21}|^2$ into the various guided modes (since the second waveguide is multi mode). The scattered power into the radiative modes can then be computed as $1-|S_{11}|^2-|S_{21}|^2$. As usual, a normalization run is required involving a straight waveguide to compute the power in the source.

The structure has mirror symmetry in the $y$ direction which can be exploited to reduce the computation size by a factor of two. This requires using `add_flux` rather than `add_mode_monitor` (which is not optimized for symmetry) and specifying the keyword argument `eig_parity=mp.ODD_Z+mp.EVEN_Y` in the call to `get_eigenmode_coefficients`. Alternatively, the waveguide could have been oriented along an arbitrary oblique direction which would require specifying `direction=mp.NO_DIRECTION` and `kpoint_func` as the waveguide axis. For an example, see [Tutorials/Eigenmode Source/Index-Guided Modes in a Ridge Waveguide](Eigenmode_Source.md#index-guided-modes-in-a-ridge-waveguide).

The simulation script is in [examples/mode-decomposition.py](https://github.com/NanoComp/meep/blob/master/python/examples/mode-decomposition.py). The notebook is [examples/mode-decomposition.ipynb](https://nbviewer.jupyter.org/github/NanoComp/meep/blob/master/python/examples/mode-decomposition.ipynb).

```py

import meep as mp

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

resolution = 25 # pixels/μm

w1 = 1.0 # width of waveguide 1

w2 = 2.0 # width of waveguide 2

Lw = 10.0 # length of waveguides 1 and 2

# lengths of waveguide taper

Lts = [2**m for m in range(4)]

dair = 3.0 # length of air region

dpml_x = 6.0 # length of PML in x direction

dpml_y = 2.0 # length of PML in y direction

sy = dpml_y+dair+w2+dair+dpml_y

Si = mp.Medium(epsilon=12.0)

boundary_layers = [mp.PML(dpml_x,direction=mp.X),

mp.PML(dpml_y,direction=mp.Y)]

lcen = 6.67 # mode wavelength

fcen = 1/lcen # mode frequency

symmetries = [mp.Mirror(mp.Y)]

R_coeffs = []

R_flux = []

for Lt in Lts:

sx = dpml_x+Lw+Lt+Lw+dpml_x

cell_size = mp.Vector3(sx,sy,0)

src_pt = mp.Vector3(-0.5*sx+dpml_x+0.2*Lw)

sources = [mp.EigenModeSource(src=mp.GaussianSource(fcen,fwidth=0.2*fcen),

center=src_pt,

size=mp.Vector3(y=sy-2*dpml_y),

eig_match_freq=True,

eig_parity=mp.ODD_Z+mp.EVEN_Y)]

# straight waveguide

vertices = [mp.Vector3(-0.5*sx-1,0.5*w1),

mp.Vector3(0.5*sx+1,0.5*w1),

mp.Vector3(0.5*sx+1,-0.5*w1),

mp.Vector3(-0.5*sx-1,-0.5*w1)]

sim = mp.Simulation(resolution=resolution,

cell_size=cell_size,

boundary_layers=boundary_layers,

geometry=[mp.Prism(vertices,height=mp.inf,material=Si)],

sources=sources,

symmetries=symmetries)

mon_pt = mp.Vector3(-0.5*sx+dpml_x+0.7*Lw)

flux = sim.add_flux(fcen,0,1,mp.FluxRegion(center=mon_pt,size=mp.Vector3(y=sy-2*dpml_y)))

sim.run(until_after_sources=mp.stop_when_fields_decayed(50,mp.Ez,mon_pt,1e-9))

res = sim.get_eigenmode_coefficients(flux,[1],eig_parity=mp.ODD_Z+mp.EVEN_Y)

incident_coeffs = res.alpha

incident_flux = mp.get_fluxes(flux)

incident_flux_data = sim.get_flux_data(flux)

sim.reset_meep()

# linear taper

vertices = [mp.Vector3(-0.5*sx-1,0.5*w1),

mp.Vector3(-0.5*Lt,0.5*w1),

mp.Vector3(0.5*Lt,0.5*w2),

mp.Vector3(0.5*sx+1,0.5*w2),

mp.Vector3(0.5*sx+1,-0.5*w2),

mp.Vector3(0.5*Lt,-0.5*w2),

mp.Vector3(-0.5*Lt,-0.5*w1),

mp.Vector3(-0.5*sx-1,-0.5*w1)]

sim = mp.Simulation(resolution=resolution,

cell_size=cell_size,

boundary_layers=boundary_layers,

geometry=[mp.Prism(vertices,height=mp.inf,material=Si)],

sources=sources,

symmetries=symmetries)

flux = sim.add_flux(fcen,0,1,mp.FluxRegion(center=mon_pt,size=mp.Vector3(y=sy-2*dpml_y)))

sim.load_minus_flux_data(flux,incident_flux_data)

sim.run(until_after_sources=mp.stop_when_fields_decayed(50,mp.Ez,mon_pt,1e-9))

res = sim.get_eigenmode_coefficients(flux,[1],eig_parity=mp.ODD_Z+mp.EVEN_Y)

taper_coeffs = res.alpha

taper_flux = mp.get_fluxes(flux)

R_coeffs.append(abs(taper_coeffs[0,0,1])**2/abs(incident_coeffs[0,0,0])**2)

R_flux.append(-taper_flux[0]/incident_flux[0])

print("refl:, {}, {:.8f}, {:.8f}".format(Lt,R_coeffs[-1],R_flux[-1]))

```

Note that the reflectance is computed for five different geometrically-scaled taper lengths: 1, 2, 4, 8, and 16 μm. A quadratic scaling of the reflectance with the taper length appears as a straight line on a log-log plot. The results are plotted using the commands below with the plot shown in the accompanying figure.

```py

if mp.am_master():

plt.figure()

plt.loglog(Lts,R_coeffs,'bo-',label='mode decomposition')

plt.loglog(Lts,R_flux,'ro-',label='Poynting flux')

plt.loglog(Lts,[0.005/Lt**2 for Lt in Lts],'k-',label=r'quadratic reference (1/Lt$^2$)')

plt.legend(loc='upper right')

plt.xlabel('taper length Lt (μm)')

plt.ylabel('reflectance')

plt.show()

```

The reflectance values computed using the two methods are nearly identical. For reference, a line with quadratic scaling is shown in black. The reflectance of the linear waveguide taper decreases quadratically with the taper length which is consistent with the analytic theory.

In the reflected-flux calculation, we apply our usual trick of first performing a reference simulation with just the incident field and then subtracting that from our taper simulation with `load_minus_flux_data`, so that what is left over is the reflected fields (from which we obtain the reflected flux). In *principle*, this trick would not be required for the mode-decomposition method, because the reflected mode is orthogonal to the forward mode and so the decomposition will separate the forward and reflected coefficients automatically. However, this is only true in the limit of infinite resolution — for a *finite* resolution, the reflected mode used for the mode coefficient calculation (calculated via MPB) is not exactly orthogonal to the forward mode propagating in Meep (whose discretization scheme is different from that of MPB). In consequence, if you did not subtract the fields of the reference simulation, the mode-coefficient could only calculate the reflected power down to a "noise floor" set by the discretization error. With the subtraction, in contrast, you can compute much smaller reflections (limited by the floating-point precision).

Diffraction Spectrum of a Binary Grating

----------------------------------------

The mode-decomposition feature can also be applied to planewaves in homogeneous media with scalar permittivity/permeability (i.e., no anisotropy). This will be demonstrated in this example to compute the diffraction spectrum of a binary phase [grating](https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Diffraction_grating). To compute the diffraction spectrum for a finite-length structure, see [Tutorials/Near to Far Field Spectra/Diffraction Spectrum of a Finite Binary Grating](Near_to_Far_Field_Spectra.md#diffraction-spectrum-of-a-finite-binary-grating). The unit cell geometry of the grating is shown in the schematic below. The grating is periodic in the $y$ direction with periodicity `gp` and has a rectangular profile of height `gh` and duty cycle `gdc`. The grating parameters are `gh`=0.5 μm, `gdc`=0.5, and `gp`=10 μm. There is a semi-infinite substrate of thickness `dsub` adjacent to the grating. The substrate and grating are glass with a refractive index of 1.5. The surrounding is air/vacuum. Perfectly matched layers (PML) of thickness `dpml` are used in the $\pm x$ boundaries.

### Transmissive Diffraction Spectrum for Planewave at Normal Incidence

A pulsed planewave with $E_z$ (or $\mathcal{S}$) polarization spanning wavelengths of 0.4 to 0.6 μm is normally incident on the grating from the glass substrate. The eigenmode monitor is placed in the air region. We will use mode decomposition to compute the transmittance — the ratio of the power in the $+x$ direction of the diffracted mode relative to that of the incident planewave — for the first ten diffraction orders. Two simulations are required: (1) an *empty* cell of homogeneous glass to obtain the incident power of the source, and (2) the grating structure to obtain the diffraction orders. At the end of the simulation, the wavelength, angle, and transmittance for each diffraction order are computed.

The simulation script is in [examples/binary_grating.py](https://github.com/NanoComp/meep/blob/master/python/examples/binary_grating.py). The notebook is [examples/binary_grating.ipynb](https://nbviewer.jupyter.org/github/NanoComp/meep/blob/master/python/examples/binary_grating.ipynb).

```py

import meep as mp

import math

import numpy as np

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

resolution = 60 # pixels/μm

dpml = 1.0 # PML thickness

dsub = 3.0 # substrate thickness

dpad = 3.0 # padding between grating and PML

gp = 10.0 # grating period

gh = 0.5 # grating height

gdc = 0.5 # grating duty cycle

sx = dpml+dsub+gh+dpad+dpml

sy = gp

cell_size = mp.Vector3(sx,sy,0)

pml_layers = [mp.PML(thickness=dpml,direction=mp.X)]

wvl_min = 0.4 # min wavelength

wvl_max = 0.6 # max wavelength

fmin = 1/wvl_max # min frequency

fmax = 1/wvl_min # max frequency

fcen = 0.5*(fmin+fmax) # center frequency

df = fmax-fmin # frequency width

src_pt = mp.Vector3(-0.5*sx+dpml+0.5*dsub,0,0)

sources = [mp.Source(mp.GaussianSource(fcen, fwidth=df),

component=mp.Ez,

center=src_pt,

size=mp.Vector3(0,sy,0))]

k_point = mp.Vector3(0,0,0)

glass = mp.Medium(index=1.5)

symmetries=[mp.Mirror(mp.Y)]

sim = mp.Simulation(resolution=resolution,

cell_size=cell_size,

boundary_layers=pml_layers,

k_point=k_point,

default_material=glass,

sources=sources,

symmetries=symmetries)

nfreq = 21

mon_pt = mp.Vector3(0.5*sx-dpml-0.5*dpad,0,0)

flux_mon = sim.add_flux(fcen,

df,

nfreq,

mp.FluxRegion(center=mon_pt, size=mp.Vector3(0,sy,0)))

sim.run(until_after_sources=mp.stop_when_fields_decayed(50, mp.Ez, mon_pt, 1e-9))

input_flux = mp.get_fluxes(flux_mon)

sim.reset_meep()

geometry = [mp.Block(material=glass,

size=mp.Vector3(dpml+dsub,mp.inf,mp.inf),

center=mp.Vector3(-0.5*sx+0.5*(dpml+dsub),0,0)),

mp.Block(material=glass,

size=mp.Vector3(gh,gdc*gp,mp.inf),

center=mp.Vector3(-0.5*sx+dpml+dsub+0.5*gh,0,0))]

sim = mp.Simulation(resolution=resolution,

cell_size=cell_size,

boundary_layers=pml_layers,

geometry=geometry,

k_point=k_point,

sources=sources,

symmetries=symmetries)

mode_mon = sim.add_flux(fcen,

df,

nfreq,

mp.FluxRegion(center=mon_pt, size=mp.Vector3(0,sy,0)))

sim.run(until_after_sources=mp.stop_when_fields_decayed(50, mp.Ez, mon_pt, 1e-9))

freqs = mp.get_eigenmode_freqs(mode_mon)

nmode = 10

res = sim.get_eigenmode_coefficients(mode_mon, range(1,nmode+1), eig_parity=mp.ODD_Z+mp.EVEN_Y)

coeffs = res.alpha

kdom = res.kdom

mode_wvl = []

mode_angle = []

mode_tran = []

for nm in range(nmode):

for nf in range(nfreq):

mode_wvl.append(1/freqs[nf])

mode_angle.append(math.degrees(math.acos(kdom[nm*nfreq+nf].x/freqs[nf])))

tran = abs(coeffs[nm,nf,0])**2/input_flux[nf]

mode_tran.append(0.5*tran if nm != 0 else tran)

print("grating{}:, {:.5f}, {:.2f}, {:.8f}".format(nm,mode_wvl[-1],mode_angle[-1],mode_tran[-1]))

```

Note the use of the keyword parameter argument `eig_parity=mp.ODD_Z+mp.EVEN_Y` in the call to `get_eigenmode_coefficients`. This is important for specifying **non-degenerate** modes in MPB since the `k_point` is (0,0,0). `ODD_Z` is for modes with $E_z$ (or $\mathcal{S}$) polarization. `EVEN_Y` is necessary since each diffraction order which is based on a given $k_x$ consists of *two* modes: one going in the $+y$ direction and the other in the $-y$ direction. `EVEN_Y` forces MPB to compute only the $+k_y + -k_y$ (cosine) mode. As a result, the total transmittance must be halved in this case to obtain the transmittance for the individual $+k_y$ or $-k_y$ mode. For `ODD_Y`, MPB will compute the $+k_y - -k_y$ (sine) mode but this will have zero power because the source is even. If the $y$ parity is left out, MPB will return a random superposition of the cosine and sine modes. Alternatively, in this example an input planewave with $H_z$ instead of $E_z$ polarization can be used which requires `eig_parity=mp.EVEN_Z+mp.ODD_Y` as well as an odd mirror symmetry plane in $y$. Finally, note the use of `add_flux` instead of `add_mode_monitor` when using symmetries.

The diffraction spectrum is then plotted and shown in the figure below.

```py

tran_max = round(max(mode_tran),1)

plt.figure()

plt.pcolormesh(np.reshape(mode_wvl,(nmode,nfreq)),

np.reshape(mode_angle,(nmode,nfreq)),

np.reshape(mode_tran,(nmode,nfreq)),

cmap='Blues',

shading='nearest',

vmin=0,

vmax=tran_max)

plt.axis([min(mode_wvl), max(mode_wvl), min(mode_angle), max(mode_angle)])

plt.xlabel("wavelength (μm)")

plt.ylabel("diffraction angle (degrees)")

plt.xticks([t for t in np.arange(0.4,0.7,0.1)])

plt.yticks([t for t in range(0,35,5)])

plt.title("transmittance of diffraction orders")

cbar = plt.colorbar()

cbar.set_ticks([t for t in np.arange(0,tran_max+0.1,0.1)])

cbar.set_ticklabels(["{:.1f}".format(t) for t in np.arange(0,tran_max+0.1,0.1)])

plt.show()

```

Each diffraction order corresponds to a single angle. In the figure below, this angle is represented by the *lower* boundary of each labeled region. For example, the $m$=0 order has a diffraction angle of 0° at all wavelengths. The representation of the diffraction orders as finite angular regions is an artifact of matplotlib's [pcolormesh](https://matplotlib.org/api/_as_gen/matplotlib.pyplot.pcolormesh.html) routine. Note that only the positive diffraction orders are shown as these are equivalent to the negative orders due to the symmetry of the source and the structure.

The diffraction orders/modes are a finite set of propagating planewaves. The wavevector $k_x$ of these modes can be computed analytically: for a frequency of $\omega$ (in $c=1$ units), these propagating modes are the **real** solutions of $\sqrt{(\omega^2 n^2 - (k_y+2\pi m/\Lambda)^2)}$ where $m$ is the diffraction order (an integer), $\Lambda$ is the periodicity of the grating, and $n$ is the refractive index of the propagating medium. In this example, $n=1$, $k_y=0$, and $\Lambda=10$ μm. Thus, at a wavelength of 0.5 μm there are a total of 20 diffraction orders of which we only computed the first 10. The wavevector $k_x$ is used to compute the angle of the diffraction order as $\cos^{-1}(k_x/(\omega n))$. (The angle can also be equivalently computed as $\sin^{-1}((k_y+2\pi m/\Lambda)/(\omega n))$.) Evanescent modes, those with an imaginary $k_x$, exist for $|m|>20$ but these modes carry no power. Note that currently Meep does not compute the number of propagating modes for you. If the mode number passed to `get_eigenmode_coefficients` is larger than the number of propagating modes at a given frequency/wavelength, MPB's Newton solver will fail to converge and will return zero for the mode coefficient. It is therefore a good idea to know beforehand the number of propagating modes.

In the limit where the grating periodicity is much larger than the wavelength and the size of the diffracting element (i.e., more than 10 times), as it is in this example, the [diffraction efficiency](https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Diffraction_efficiency) can be computed analytically using scalar theory. This is described in the OpenCourseWare [Optics course](https://ocw.mit.edu/courses/mechanical-engineering/2-71-optics-spring-2009/) in the Lecture 16 (Gratings: Amplitude and Phase, Sinusoidal and Binary) [notes](https://ocw.mit.edu/courses/mechanical-engineering/2-71-optics-spring-2009/video-lectures/lecture-16-gratings-amplitude-and-phase-sinusoidal-and-binary/MIT2_71S09_lec16.pdf) and [video](https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=JmWguqCZRxk). For a review of scalar diffraction theory, see Chapter 3 ("Analysis of Two-Dimensional Signals and Systems") of [Introduction to Fourier Optics (fourth edition)](https://www.amazon.com/Introduction-Fourier-Optics-Joseph-Goodman-ebook/dp/B076TBP48F) by J.W. Goodman. From the scalar theory, the diffraction efficiency of the binary grating is $4/(m\pi)^2$ when the phase difference between the propagating distance in the glass relative to the same distance in air is $\pi$. The phase difference/contrast is $(2\pi/\lambda)(n-1)s$ where $\lambda$ is the wavelength, $n$ is the refractive index of the grating, and $s$ is the propagation distance in the grating (`gh` in the script). A special feature of the binary phase grating is that the diffraction efficiency is 0 for all *even* orders. This is verified by the diffraction spectrum shown above at $\lambda=0.5$ μm. Note the wavelength dependence of the transmittance and, in particular, the slightly *non-zero* diffraction efficiency for the even orders at wavelengths other than 0.5 μm. Since the diffraction efficiency of the ninth order has already fallen to a negligible value (~0.005), computing the spectra of higher-order modes is unnecessary.

To convert the diffraction efficiency into transmittance in the $x$ direction (in order to be able to compare the scalar-theory results with those from Meep), the diffraction efficiency must be multiplied by the Fresnel transmittance from air to glass and by the cosine of the diffraction angle. We compare the analytic and simulated results at a wavelength of 0.5 μm for diffraction orders 1 (2.9°), 3 (8.6°), 5 (14.5°), and 7 (20.5°). The analytic results are 0.3886, 0.0427, 0.0151, and 0.0074. The Meep results are 0.3891, 0.04287, 0.0152, and 0.0076. This corresponds to relative errors of approximately 1.3%, 0.4%, 0.8%, and 2.1% which indicates good agreement.

Finally, by investigating the transmittance of the zeroth order (at a wavelength of 0.5 μm) in the limit as the grating periodicity approaches zero, we can demonstrate the breakdown of the scalar theory in the wavelength-scale regime which can only be solved using a full-wave method. When the periodicity is much less than the wavelength (i.e., subwavelength), the transmittance can again be solved analytically using effective-medium theory involving a three-layer structure: a layer of the averaged $\varepsilon$ (mean or harmonic mean depending on the polarization $E_z$ or $H_z$) sandwiched between the glass substrate and air. Results are shown in the following figure.

Starting around a grating periodicity of 1.0 μm, the transmittance is no longer zero and increases rapidly with decreasing periodicity. As shown in the inset, for periodicities less than 0.5 μm, the transmittance converges to its asymptotic limit determined by the effective-medium theory: 0.99744 for the $E_z$ and 0.99057 for the $H_z$ polarization. The weak polarization dependence is due to the low index contrast. The oscillations in the data are real and *not* an artifact of the discretization. For example, note the "hump" in the transmittance spectra for the $E_z$ polarization near a grating periodicity of 1.0 μm (twice the wavelength). This feature is associated with a "Wood anomaly" (see e.g. [Hessel and Oliner, 1965](https://www.osapublishing.org/ao/abstract.cfm?uri=ao-4-10-1275)), which occurs when new diffracted orders appear in the far field; for normal incidence, new diffraction orders appear as the period goes through any multiple of the wavelength.

### Reflectance and Transmittance Spectra for Planewave at Oblique Incidence

As an additional demonstration of the mode-decomposition feature, the reflectance and transmittance of all diffracted orders for any grating with no material absorption and a planewave source incident at any arbitrary angle and wavelength must necessarily sum to unity. Also, the total reflectance and transmittance must be equivalent to values computed using the Poynting flux. This demonstration is somewhat similar to the [single-mode waveguide example](#reflectance-of-a-waveguide-taper).

The following script is adapted from the previous binary-grating example involving a [normally-incident planewave](#transmittance-spectra-for-planewave-at-normal-incidence). The total reflectance, transmittance, and their sum are displayed at the end of the simulation on two separate lines prefixed by `mode-coeff:` and `poynting-flux:`.

Results are computed for a single wavelength of 0.5 μm. The pulsed planewave is incident at an angle of 10.7°. Its spatial profile is defined using the source amplitude function `pw_amp`. This [anonymous function](https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Anonymous_function) takes two arguments, the wavevector and a point in space (both `mp.Vector3`s), and returns a function of one argument which defines the planewave amplitude at that point. Even though we are computing the reflectance and transmittance at a single wavelength, the choice of the bandwidth of the pulsed source is important. This is because a broad-bandwidth source generates glancing-angle waves which are poorly absorbed by the PML (or by an absorber) which in turn prevents the simulation from terminating as the fields do not decay away. The solution is to use a narrow-bandwidth pulse which limits the generation of glancing-angle waves. Because launching glancing-angle waves is generally unavoidable, the `sim.run(until_after_sources=mp.stop_when_fields_decayed(...))` termination criteria is replaced with a fixed runtime via `sim.run(until_after_sources=200)`. As a general rule of thumb, the more oblique the planewave source, the longer the run time required to ensure accurate results. There is an additional line monitor between the source and the grating for computing the reflectance. The angle of each reflected/transmitted mode, which can be positive or negative, is computed using its dominant planewave vector. Since the oblique source breaks the symmetry in the $y$ direction, each diffracted order must be computed separately. In total, there are 59 reflected and 39 transmitted orders.

The simulation script is in [examples/binary_grating_oblique.py](https://github.com/NanoComp/meep/blob/master/python/examples/binary_grating_oblique.py). The notebook is [examples/binary_grating_oblique.ipynb](https://nbviewer.jupyter.org/github/NanoComp/meep/blob/master/python/examples/binary_grating_oblique.ipynb).

```py

import meep as mp

import math

import cmath

import numpy as np

resolution = 50 # pixels/μm

dpml = 1.0 # PML thickness

dsub = 3.0 # substrate thickness

dpad = 3.0 # length of padding between grating and PML

gp = 10.0 # grating period

gh = 0.5 # grating height

gdc = 0.5 # grating duty cycle

sx = dpml+dsub+gh+dpad+dpml

sy = gp

cell_size = mp.Vector3(sx,sy,0)

pml_layers = [mp.PML(thickness=dpml,direction=mp.X)]

wvl = 0.5 # center wavelength

fcen = 1/wvl # center frequency

df = 0.05*fcen # frequency width

ng = 1.5

glass = mp.Medium(index=ng)

use_cw_solver = False # CW solver or time stepping?

tol = 1e-6 # CW solver tolerance

max_iters = 2000 # CW solver max iterations

L = 10 # CW solver L

# rotation angle of incident planewave

# counter clockwise (CCW) about Z axis, 0 degrees along +X axis

theta_in = math.radians(10.7)

# k (in source medium) with correct length (plane of incidence: XY)

k = mp.Vector3(fcen*ng).rotate(mp.Vector3(z=1), theta_in)

symmetries = []

eig_parity = mp.ODD_Z

if theta_in == 0:

k = mp.Vector3(0,0,0)

symmetries = [mp.Mirror(mp.Y)]

eig_parity += mp.EVEN_Y

def pw_amp(k,x0):

def _pw_amp(x):

return cmath.exp(1j*2*math.pi*k.dot(x+x0))

return _pw_amp

src_pt = mp.Vector3(-0.5*sx+dpml+0.3*dsub,0,0)

sources = [mp.Source(mp.ContinuousSource(fcen,fwidth=df) if use_cw_solver else mp.GaussianSource(fcen,fwidth=df),

component=mp.Ez,

center=src_pt,

size=mp.Vector3(0,sy,0),

amp_func=pw_amp(k,src_pt))]

sim = mp.Simulation(resolution=resolution,

cell_size=cell_size,

boundary_layers=pml_layers,

k_point=k,

default_material=glass,

sources=sources,

symmetries=symmetries)

refl_pt = mp.Vector3(-0.5*sx+dpml+0.5*dsub,0,0)

refl_flux = sim.add_flux(fcen, 0, 1, mp.FluxRegion(center=refl_pt, size=mp.Vector3(0,sy,0)))

if use_cw_solver:

sim.init_sim()

sim.solve_cw(tol, max_iters, L)

else:

sim.run(until_after_sources=100)

input_flux = mp.get_fluxes(refl_flux)

input_flux_data = sim.get_flux_data(refl_flux)

sim.reset_meep()

geometry = [mp.Block(material=glass,

size=mp.Vector3(dpml+dsub,mp.inf,mp.inf),

center=mp.Vector3(-0.5*sx+0.5*(dpml+dsub),0,0)),

mp.Block(material=glass,

size=mp.Vector3(gh,gdc*gp,mp.inf),

center=mp.Vector3(-0.5*sx+dpml+dsub+0.5*gh,0,0))]

sim = mp.Simulation(resolution=resolution,

cell_size=cell_size,

boundary_layers=pml_layers,

geometry=geometry,

k_point=k,

sources=sources,

symmetries=symmetries)

refl_flux = sim.add_flux(fcen, 0, 1, mp.FluxRegion(center=refl_pt, size=mp.Vector3(0,sy,0)))

sim.load_minus_flux_data(refl_flux,input_flux_data)

tran_pt = mp.Vector3(0.5*sx-dpml-0.5*dpad,0,0)

tran_flux = sim.add_flux(fcen, 0, 1, mp.FluxRegion(center=tran_pt, size=mp.Vector3(0,sy,0)))

if use_cw_solver:

sim.init_sim()

sim.solve_cw(tol, max_iters, L)

else:

sim.run(until_after_sources=200)

nm_r = np.floor((fcen*ng-k.y)*gp)-np.ceil((-fcen*ng-k.y)*gp) # number of reflected orders

if theta_in == 0:

nm_r = nm_r/2 # since eig_parity removes degeneracy in y-direction

nm_r = int(nm_r)

res = sim.get_eigenmode_coefficients(refl_flux, range(1,nm_r+1), eig_parity=eig_parity)

r_coeffs = res.alpha

Rsum = 0

for nm in range(nm_r):

r_kdom = res.kdom[nm]

Rmode = abs(r_coeffs[nm,0,1])**2/input_flux[0]

r_angle = np.sign(r_kdom.y)*math.acos(r_kdom.x/(ng*fcen))

print("refl:, {:2d}, {:6.2f}, {:.8f}".format(nm,math.degrees(r_angle),Rmode))

Rsum += Rmode

nm_t = np.floor((fcen-k.y)*gp)-np.ceil((-fcen-k.y)*gp) # number of transmitted orders

if theta_in == 0:

nm_t = nm_t/2 # since eig_parity removes degeneracy in y-direction

nm_t = int(nm_t)

res = sim.get_eigenmode_coefficients(tran_flux, range(1,nm_t+1), eig_parity=eig_parity)

t_coeffs = res.alpha

Tsum = 0

for nm in range(nm_t):

t_kdom = res.kdom[nm]

Tmode = abs(t_coeffs[nm,0,0])**2/input_flux[0]

t_angle = np.sign(t_kdom.y)*math.acos(t_kdom.x/fcen)

print("tran:, {:2d}, {:6.2f}, {:.8f}".format(nm,math.degrees(t_angle),Tmode))

Tsum += Tmode

print("mode-coeff:, {:.6f}, {:11.6f}, {:.6f}".format(Rsum,Tsum,Rsum+Tsum))

r_flux = mp.get_fluxes(refl_flux)

t_flux = mp.get_fluxes(tran_flux)

Rflux = -r_flux[0]/input_flux[0]

Tflux = t_flux[0]/input_flux[0]

print("poynting-flux:, {:.6f}, {:.6f}, {:.6f}".format(Rflux,Tflux,Rflux+Tflux))

```

Since this is a single-wavelength calculation, the [frequency-domain solver](../Python_User_Interface.md#frequency-domain-solver) can be used instead of time stepping for a possible performance enhancement. The only changes necessary to the original script are to replace two objects: (1) `GaussianSource` with `ContinuousSource` and (2) `run` with `solve_cw`. Choosing which approach to use is determined by the `use_cw_solver` boolean variable. In this example, mainly because of the oblique source, the frequency-domain solver converges slowly and is less efficient than the time-stepping simulation. The results from both approaches are nearly identical. Time stepping is therefore the default.

The following are several lines of output for eight of the reflected and transmitted orders. The first numerical column is the mode number, the second is the mode angle (in degrees), and the third is the fraction of the input power that is concentrated in the mode. Note that the thirteenth transmitted order at 19.18° contains nearly 38% of the input power.

```

...

refl:, 7, 6.83, 0.00006645

refl:, 8, -8.49, 0.00005695

refl:, 9, 8.76, 0.00015756

refl:, 10, -10.43, 0.00001272

refl:, 11, 10.70, 0.04414669

refl:, 12, -12.38, 0.00005969

refl:, 13, 12.65, 0.00041535

refl:, 14, -14.34, 0.00001986

...

```

```

...

tran:, 12, -18.75, 0.00095438

tran:, 13, 19.18, 0.38260804

tran:, 14, -21.81, 0.00198524

tran:, 15, 22.24, 0.00107212

tran:, 16, -24.93, 0.00098416

tran:, 17, 25.37, 0.04148390

tran:, 18, -28.13, 0.00137340

tran:, 19, 28.59, 0.00113876

...

```

The mode number is equivalent to the band index from the MPB calculation. The ordering of the modes is according to *decreasing* values of $k_x$. The first mode has the largest $k_x$ and thus angle closest to 0°. As a corollary, the first mode has the smallest $|k_y+2\pi m/\lambda|$. For a non-zero $k_y$ (as in the case of an obliquely incident source), this expression will not necessarily be zero. The first seven reflected modes have $m$ values of -3, -4, -2, -5, -1, -6, and 0. These $m$ values are not monotonic. This is because $k_x$ is a nonlinear function of $m$ as shown earlier. The ordering of the transmitted modes is different since these modes are in vacuum and not glass (recall that the medium's refractive index is also a part of this nonlinear function). In the first example involving a normally incident source with $k_y = 0$, the ordering of the modes is monotonic: $m = 0, \pm 1, \pm 2, \dotsc$

The two main lines of the output are:

```

mode-coeff:, 0.061007, 0.937897, 0.998904

poynting-flux:, 0.061063, 0.938384, 0.999447

```

The first numerical column is the total reflectance, the second is the total transmittance, and the third is their sum. Results from the mode coefficients agree with the Poynting flux values to three decimal places. Also, the total reflectance and transmittance sum to unity. These results indicate that approximately 6% of the input power is reflected and the remaining 94% is transmitted.

### Diffracted Planewaves in Homogeneous Media

Rather than specify the diffracted planewave in homogeneous media using a band number (which is a property of the eigensolver), we can specify it directly using a [`DiffractedPlanewave`](../Python_User_Interface.md#diffractedplanewave). This is the only approach in 3d for specifying *non-degenerate* modes and is particularly useful when the incident planewave is oblique since in this case the band number does not directly relate to the diffraction order, as demonstrated previously. As diffracted planewaves are generally not mirror symmetric (because the grating itself is not symmetric or the planewave source is incident at an oblique angle), `DiffractedPlanewave` cannot take advantage of `symmetries` that bisect the monitor plane which means that it can only be used with `add_mode_monitor` rather than `add_flux`. A `DiffractedPlanewave` object can be passed as the `bands` argument of `get_eigenmode_coefficients` (or the `band_num` argument of `get_eigenmode`) and its constructor has four arguments: (1) a list/tuple of integers for the diffraction order, (2) a `Vector3` for the axis which together with the planewave's wavevector defines the "plane of incidence", and complex amplitudes for the (3) $\mathcal{S}$ and (4) $\mathcal{P}$ polarizations (i.e., electric field perpendicular or parallel to the plane of incidence, respectively). `DiffractedPlanewave` only computes *non-evanescent* propagating modes (i.e., the component of the wavevector in the non-periodic direction is real valued). For evanescent modes, a warning will be displayed and `get_eigenmode_coefficients` will return an empty object.

As a demonstration, the [previous example](#reflectance-and-transmittance-spectra-for-planewave-at-oblique-incidence) involving a binary grating with an input planewave at oblique incidence is modified such that the transmitted diffraction orders are computed using two different methods: (1) MPB's eigensolver and (2) `DiffractedPlanewave`. This example verifies that (1) both methods compute the same set of diffracted modes (although the ordering is different when the source is oblique) and (2) that the total power in all the orders is equivalent to the Poynting flux.

Shown below is the relevant section of the simulation involving the computation of the diffracted orders and their transmittance. The full simulation script is in [examples/diffracted_planewave.py](https://github.com/NanoComp/meep/blob/master/python/examples/diffracted_planewave.py).

```py

# number of (non-evanescent) transmitted orders

nm_t = np.floor((fcen-k.y)*gp)-np.ceil((-fcen-k.y)*gp)

if theta_in == 0:

nm_t = nm_t/2

nm_t = int(nm_t)+1

bands = range(1,nm_t+1)

if theta_in == 0:

orders = range(0,nm_t)

else:

orders = range(int(np.ceil((-fcen-k.y)*gp)),int(np.floor((fcen-k.y)*gp))+1)

eig_sum = 0

dp_sum = 0

for band,order in zip(bands,orders):

res = sim.get_eigenmode_coefficients(tran_mon, [band], eig_parity=eig_parity)

if res is not None:

tran_eig = abs(res.alpha[0,0,0])**2/input_flux[0]

if theta_in == 0:

tran_eig = 0.5*tran_eig

else:

tran_eig = 0

eig_sum += tran_eig

res = sim.get_eigenmode_coefficients(tran_mon,

mp.DiffractedPlanewave((0,order,0),mp.Vector3(0,1,0),0,1))

if res is not None:

tran_dp = abs(res.alpha[0,0,0])**2/input_flux[0]

if (theta_in == 0) and (order == 0):

tran_dp = 0.5*tran_dp

else:

tran_dp = 0

dp_sum += tran_dp

if theta_in == 0:

err = abs(tran_eig-tran_dp)/tran_eig

print("tran:, {:2d}, {:.8f}, {:2d}, {:.8f}, {:.8f}".format(band,tran_eig,order,tran_dp,err))

else:

print("tran:, {:2d}, {:.8f}, {:2d}, {:.8f}".format(band,tran_eig,order,tran_dp))

flux = mp.get_fluxes(tran_mon)

t_flux = flux[0]/input_flux[0]

if (theta_in == 0):

t_flux = 0.5*t_flux

err = abs(dp_sum-t_flux)/t_flux

print("flux:, {:.8f}, {:.8f}, {:.8f}, {:.8f}".format(eig_sum,

dp_sum,

t_flux,

err))

```

There are four items to note regarding the use of `DiffractedPlanewave`: (1) the diffraction order `(0,order,0)` contains non-zero elements for only the $d-1$ periodic directions of the $d$ dimensional cell (which is just the $y$ direction in this example), (2) specifying properties of the eigensolver including `eig_parity`, `eig_resolution`, `eig_tolerance`, and `kpoint_func` as part of the call to `get_eigenmode_coefficients` is not necessary (and is ignored), (3) in 2d, the `axis` is chosen as `Vector3(0,1,0)` (the direction parallel to the source) although *any* vector in the $xy$ plane that is not parallel to the mode's wavevector is also valid, and (4) since the source has $H_z$ polarization (not shown), the $\mathcal{S}$ polarization amplitude is 0 and the $\mathcal{P}$ polarization is 1.

Results of this calculation are shown below for two different grating configurations:

1. `gp`=2.6 μm, `gh`=0.4 μm, `gdc`=0.3 μm, incident angle of 0°

2. `gp`=3.7 μm, `gh`=0.6 μm, `gdc`=0.4 μm, incident angle of 13.5°

In the first configuration, the output on each line prefixed by `tran:,` consists of five values: the band index, transmittance of the diffracted planewave obtained using the eigensolver, the diffraction order, transmittance of the diffracted planewave obtained using `DiffractedPlanewave`, and relative error of the transmittance. As can be seen by the transmittance values on each line, there is a direct relationship between the band number and the diffraction order (i.e., band number 1 corresponds to diffraction order 0, band number 2 with diffraction order 1, etc.) because the input planewave is normally incident. The last line prefixed by `flux:,` lists the total power obtained using the eigensolver, `DiffractedPlanewave`, Poynting flux, and relative error of the `DiffractedPlanewave` result with respect to the Poynting flux.

```

tran:, 1, 0.12695973, 0, 0.12696027, 0.00000428

tran:, 2, 0.24552342, 1, 0.24552348, 0.00000025

tran:, 3, 0.07401465, 2, 0.07401465, 0.00000002

tran:, 4, 0.00793261, 3, 0.00793262, 0.00000078

tran:, 5, 0.01094389, 4, 0.01094389, 0.00000010

tran:, 6, 0.01361924, 5, 0.01362885, 0.00070525

flux:, 0.47899353, 0.47900375, 0.47898568, 0.00003772

```

In the second configuration, the output is similar to the first configuration with the only difference being the lines prefixed by `tran:,` do not include the relative error as the final column. Whereas in the first configuration the transmittance for the two methods is nearly equivalent on each line, this is not the case in the second configuration since the incident planewave is oblique. Although the order of the diffracted modes is different (i.e., band number 1 corresponds to diffraction order $m=-3$, band number 2 with diffraction order $m=-2$, band number 3 with $m=-4$, etc.), the total power in all the modes is equivalent for all three methods.

```

tran:, 1, 0.02879456, -9, 0.00594139

tran:, 2, 0.02505013, -8, 0.00615678

tran:, 3, 0.01737490, -7, 0.00709585

tran:, 4, 0.32428997, -6, 0.01121764

tran:, 5, 0.00957856, -5, 0.00957870

tran:, 6, 0.09070071, -4, 0.01737485

tran:, 7, 0.01121627, -3, 0.02879462

tran:, 8, 0.29570513, -2, 0.02505018

tran:, 9, 0.00709584, -1, 0.32429003

tran:, 10, 0.03461314, 0, 0.09070063

tran:, 11, 0.00615701, 1, 0.29570530

tran:, 12, 0.02832782, 2, 0.03461314

tran:, 13, 0.00594127, 3, 0.02832783

tran:, 14, 0.02346054, 4, 0.0234605

flux:, 0.90830587, 0.90830748, 0.90911585, 0.00088919

```

Diffracted Orders of a Triangular/Hexagonal Lattice

---------------------------------------------------

While it is straightforward to compute the diffracted orders of a square lattice, a triangular/hexagonal lattice requires some care. This is because Meep only supports a rectilinear cell lattice. It is therefore not possible to directly simulate the unit cell of a triangular lattice. The workaround is to use a (rectilinear) *supercell* but then the diffracted orders must be defined differently in order to correspond exactly to those of the actual unit cell. This is because the supercell introduces artificial diffraction orders (forbidden by the higher symmetry of the underlying triangular lattice) that carry no power. As a demonstration, we will compute the transmitted orders of a 2D grating with triangular lattice. We will verify that only the "real" orders contain nonzero power whereas the artificial ones contain zero power.

As shown in the left side of the figure below, the lattice vectors of a triangular lattice are $\vec{a_1} = (\Lambda,0)$ and $\vec{a_2}=(\frac{\Lambda}{2},\frac{\sqrt{3}}{2}\Lambda)$ where $\Lambda$ is the lattice periodicity. The unit cell is marked by the dotted silver line. The [reciprocal lattice vectors](https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Reciprocal_lattice#Two_dimensions) are $\vec{b_1}=\frac{2\pi}{\Lambda}(1,-1/\sqrt{3})$ and $\vec{b_2}=\frac{2\pi}{\Lambda}(0,2/\sqrt{3})$. An in-plane ($xy$) diffracted order of the unit cell can be defined as $\vec{k_\parallel}=m_1\vec{b_1}+m_2\vec{b_2}$ where $m_1$ and $m_2$ are integers.

For the supercell shown in the right side of the figure, the lattice vectors are $\vec{a_1} = (\Lambda,0)$ and $\vec{a_3} = (0,\sqrt{3}\Lambda)$. Its reciprocal lattice vectors are $\vec{b'_1}=\frac{2\pi}{\Lambda}(1,0)$ and $\vec{b'_2}=\frac{2\pi}{\Lambda}(0,1/\sqrt{3})$. Note that the dot product of $\vec{b'_1}$ and $\vec{b'_2}$ is zero because they are orthogonal. An in-plane diffracted order of the supercell can be defined as $\vec{k_{SC}}=n_1\vec{b'_1}+n_2\vec{b'_2}$ where $n_1$ and $n_2$ are integers.

Given a "real" diffracted order specified by $(m_1,m_2)$, we need to determine the equivalent order of the supercell specified by $(n_1,n_2)$ for use in the simulation when computing the mode coefficients. Setting $\vec{k_{SC}}=\vec{k_\parallel}$ and solving for the pair of equations yields: $n_1=m_1$ and $n_2=-m_1+2m_2$.

To demonstrate this in practice, we will compute the power (an absolute quantity) of the $(0,1)$ order of a triangular lattice of cylindrical rods (height: 0.5 µm, radius: 0.1 µm) on a glass ($n=1.5$) substrate with periodicity of 1.0 µm. Note that this is a 3D simulation. In this example, the plane of incidence is $yz$ and the $E_x$ source therefore corresponds to the $\mathcal{S}$ polarization.

The simulation script is in [examples/grating2d_triangular_lattice.py](https://github.com/NanoComp/meep/blob/master/python/examples/grating2d_triangular_lattice.py).

```py

import meep as mp

import math

import numpy as np

resolution = 100 # pixels/μm

ng = 1.5

glass = mp.Medium(index=ng)

wvl = 0.5 # wavelength

fcen = 1/wvl

# rectangular supercell

sx = 1.0

sy = np.sqrt(3)

dpml = 1.0 # PML thickness

dsub = 2.0 # substrate thickness

dair = 2.0 # air padding

hcyl = 0.5 # cylinder height

rcyl = 0.1 # cylinder radius

sz = dpml+dsub+hcyl+dair+dpml

cell_size = mp.Vector3(sx,sy,sz)

boundary_layers = [mp.PML(thickness=dpml,direction=mp.Z)]

# periodic boundary conditions

k_point = mp.Vector3()

src_pt = mp.Vector3(0,0,-0.5*sz+dpml)

sources = [mp.Source(src=mp.GaussianSource(fcen,fwidth=0.1*fcen),

size=mp.Vector3(sx,sy,0),

center=src_pt,

component=mp.Ex)]

substrate = [mp.Block(size=mp.Vector3(mp.inf,mp.inf,dpml+dsub),

center=mp.Vector3(0,0,-0.5*sz+0.5*(dpml+dsub)),

material=glass)]

cyl_grating = [mp.Cylinder(center=mp.Vector3(0,0,-0.5*sz+dpml+dsub+0.5*hcyl),

radius=rcyl,

height=hcyl,

material=glass),

mp.Cylinder(center=mp.Vector3(0.5*sx,0.5*sy,-0.5*sz+dpml+dsub+0.5*hcyl),

radius=rcyl,

height=hcyl,

material=glass),

mp.Cylinder(center=mp.Vector3(-0.5*sx,0.5*sy,-0.5*sz+dpml+dsub+0.5*hcyl),

radius=rcyl,

height=hcyl,

material=glass),

mp.Cylinder(center=mp.Vector3(-0.5*sx,-0.5*sy,-0.5*sz+dpml+dsub+0.5*hcyl),

radius=rcyl,

height=hcyl,

material=glass),

mp.Cylinder(center=mp.Vector3(0.5*sx,-0.5*sy,-0.5*sz+dpml+dsub+0.5*hcyl),

radius=rcyl,

height=hcyl,

material=glass)]

geometry = substrate + cyl_grating

sim = mp.Simulation(resolution=resolution,

cell_size=cell_size,

sources=sources,

geometry=geometry,

boundary_layers=boundary_layers,

k_point=k_point)

tran_pt = mp.Vector3(0,0,0.5*sz-dpml)

tran_flux = sim.add_mode_monitor(fcen,

0,

1,

mp.ModeRegion(center=tran_pt,

size=mp.Vector3(sx,sy,0)))

sim.run(until_after_sources=mp.stop_when_fields_decayed(20,mp.Ex,src_pt,1e-6))

# unit cell (triangular lattice)

mx = 0 # diffraction order in x direction

my = 1 # diffraction order in y direction

# check: for diffraction orders of supercell for which

# nx = mx and ny = -mx + 2*my and thus

# only even orders should produce nonzero power

nx = mx

for ny in range(4):

kz2 = fcen**2-(nx/sx)**2-(ny/sy)**2

if kz2 > 0:

res = sim.get_eigenmode_coefficients(tran_flux,

mp.DiffractedPlanewave((nx,ny,0),

mp.Vector3(0,1,0),

1,

0))

t_coeffs = res.alpha

tran = abs(t_coeffs[0,0,0])**2

print("order:, {}, {}, {:.5f}".format(nx,ny,tran))

```

The output lists the power in the orders labeled by $n_1$ and $n_2$. Because $n_1=m_1$ and $n_2=-m_1+2m_2$, only those supercell orders with even $n_2$ contain nonzero power whereas the odd orders (artifacts of the supercell) contain zero power. Note that the $(m_1,m_2)=(0,1)$ order of the unit cell corresponds to the $(n_1,n_2)=(0,2)$ order of the supercell.

```

order:, 0, 0, 1.46914

order:, 0, 1, 0.00000

order:, 0, 2, 0.03570

order:, 0, 3, 0.00000

```

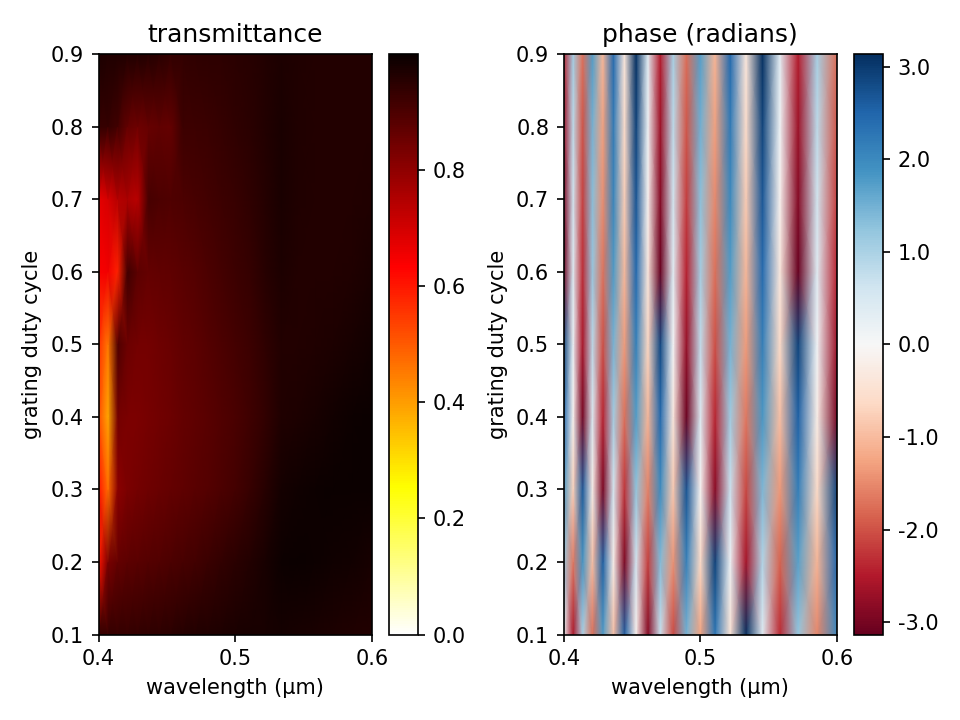

Phase Map of a Subwavelength Binary Grating

-------------------------------------------

We can also use the complex mode coefficients to compute the phase (or impedance) of the diffraction orders. This can be used to generate a phase map of the binary grating as a function of its geometric parameters. Phase maps are important for the design of subwavelength phase shifters such as those used in a metasurface lens. When the period of the unit cell is subwavelength, the zeroth-diffraction order is the only propagating wave. In this demonstration, which is adapted from the previous example, we compute the transmittance spectra and phase map of the zeroth-diffraction order (at 0°) for an $E_z$-polarized planewave pulse spanning wavelengths of 0.4 to 0.6 μm which is normally incident on a binary grating with a periodicity of 0.35 μm and height of 0.6 μm. The duty cycle of the grating is varied from 0.1 to 0.9 in separate runs.

The simulation script is in [examples/binary_grating_phasemap.py](https://github.com/NanoComp/meep/blob/master/python/examples/binary_grating_phasemap.py). The notebook is [examples/binary_grating_phasemap.ipynb](https://nbviewer.jupyter.org/github/NanoComp/meep/blob/master/python/examples/binary_grating_phasemap.ipynb).

```py

import meep as mp

import numpy as np

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

import numpy.matlib

import argparse

resolution = 60 # pixels/μm

dpml = 1.0 # PML thickness

dsub = 3.0 # substrate thickness

dpad = 3.0 # padding between grating and PML

wvl_min = 0.4 # min wavelength

wvl_max = 0.6 # max wavelength

fmin = 1/wvl_max # min frequency

fmax = 1/wvl_min # max frequency

fcen = 0.5*(fmin+fmax) # center frequency

df = fmax-fmin # frequency width

nfreq = 21 # number of frequency bins

k_point = mp.Vector3(0,0,0)

glass = mp.Medium(index=1.5)

def grating(gp,gh,gdc,oddz):

sx = dpml+dsub+gh+dpad+dpml

sy = gp

cell_size = mp.Vector3(sx,sy,0)

pml_layers = [mp.PML(thickness=dpml,direction=mp.X)]

src_pt = mp.Vector3(-0.5*sx+dpml+0.5*dsub,0,0)

sources = [mp.Source(mp.GaussianSource(fcen, fwidth=df), component=mp.Ez if oddz else mp.Hz, center=src_pt, size=mp.Vector3(0,sy,0))]

symmetries=[mp.Mirror(mp.Y, phase=+1 if oddz else -1)]

sim = mp.Simulation(resolution=resolution,

cell_size=cell_size,

boundary_layers=pml_layers,

k_point=k_point,

default_material=glass,

sources=sources,

symmetries=symmetries)

mon_pt = mp.Vector3(0.5*sx-dpml-0.5*dpad,0,0)

flux_mon = sim.add_flux(fcen, df, nfreq, mp.FluxRegion(center=mon_pt, size=mp.Vector3(0,sy,0)))

sim.run(until_after_sources=100)

input_flux = mp.get_fluxes(flux_mon)

sim.reset_meep()

geometry = [mp.Block(material=glass, size=mp.Vector3(dpml+dsub,mp.inf,mp.inf), center=mp.Vector3(-0.5*sx+0.5*(dpml+dsub),0,0)),

mp.Block(material=glass, size=mp.Vector3(gh,gdc*gp,mp.inf), center=mp.Vector3(-0.5*sx+dpml+dsub+0.5*gh,0,0))]

sim = mp.Simulation(resolution=resolution,

cell_size=cell_size,

boundary_layers=pml_layers,

geometry=geometry,

k_point=k_point,

sources=sources,

symmetries=symmetries)

mode_mon = sim.add_flux(fcen, df, nfreq, mp.FluxRegion(center=mon_pt, size=mp.Vector3(0,sy,0)))

sim.run(until_after_sources=300)

freqs = mp.get_eigenmode_freqs(mode_mon)

res = sim.get_eigenmode_coefficients(mode_mon, [1], eig_parity=mp.ODD_Z+mp.EVEN_Y if oddz else mp.EVEN_Z+mp.ODD_Y)

coeffs = res.alpha

mode_wvl = [1/freqs[nf] for nf in range(nfreq)]

mode_tran = [abs(coeffs[0,nf,0])**2/input_flux[nf] for nf in range(nfreq)]

mode_phase = [np.angle(coeffs[0,nf,0]) for nf in range(nfreq)]

return mode_wvl, mode_tran, mode_phase

if __name__ == '__main__':

parser = argparse.ArgumentParser()

parser.add_argument('-gp', type=float, default=0.35, help='grating periodicity (default: 0.35 μm)')

parser.add_argument('-gh', type=float, default=0.6, help='grating height (default: 0.6 μm)')

parser.add_argument('-oddz', action='store_true', default=False, help='oddz? (default: False)')

args = parser.parse_args()

gdc = np.arange(0.1,1.0,0.1)

mode_tran = np.empty((gdc.size,nfreq))

mode_phase = np.empty((gdc.size,nfreq))

for n in range(gdc.size):

mode_wvl, mode_tran[n,:], mode_phase[n,:] = grating(args.gp,args.gh,gdc[n],args.oddz)

plt.figure(dpi=150)

plt.subplot(1,2,1)

plt.pcolormesh(mode_wvl, gdc, mode_tran, cmap='hot_r', shading='gouraud', vmin=0, vmax=mode_tran.max())

plt.axis([wvl_min, wvl_max, gdc[0], gdc[-1]])

plt.xlabel("wavelength (μm)")

plt.xticks([t for t in np.arange(wvl_min,wvl_max+0.1,0.1)])

plt.ylabel("grating duty cycle")

plt.yticks([t for t in np.arange(gdc[0],gdc[-1]+0.1,0.1)])

plt.title("transmittance")

cbar = plt.colorbar()

cbar.set_ticks([t for t in np.arange(0,1.2,0.2)])

cbar.set_ticklabels(["{:.1f}".format(t) for t in np.arange(0,1.2,0.2)])

plt.subplot(1,2,2)

plt.pcolormesh(mode_wvl, gdc, mode_phase, cmap='RdBu', shading='gouraud', vmin=mode_phase.min(), vmax=mode_phase.max())

plt.axis([wvl_min, wvl_max, gdc[0], gdc[-1]])

plt.xlabel("wavelength (μm)")

plt.xticks([t for t in np.arange(wvl_min,wvl_max+0.1,0.1)])

plt.ylabel("grating duty cycle")

plt.yticks([t for t in np.arange(gdc[0],gdc[-1]+0.1,0.1)])

plt.title("phase (radians)")

cbar = plt.colorbar()

cbar.set_ticks([t for t in range(-3,4)])

cbar.set_ticklabels(["{:.1f}".format(t) for t in range(-3,4)])

plt.tight_layout()

plt.show()

```

The phase of the zeroth-diffraction order is simply the angle of its complex mode coefficient. Note that it is generally only the relative phase (the phase difference) between different structures that is useful. The overall mode coefficient $\alpha$ is multiplied by a complex number given by the source amplitude, as well as an arbitrary (but deterministic) phase choice by the mode solver MPB (i.e., which maximizes the energy in the real part of the fields via [`ModeSolver.fix_field_phase`](https://mpb.readthedocs.io/en/latest/Python_User_Interface/#loading-and-manipulating-the-current-field)) — but as long as you keep the current source fixed as you vary the parameters of the structure, the relative phases are meaningful.

The script is run from the shell terminal using: `python binary_grating_phasemap.py -gp 0.35 -gh 0.6 -oddz`. The figure below shows the transmittance spectra (left) and phase map (right). The transmittance is nearly unity over most of the parameter space mainly because of the subwavelength dimensions of the grating. The phase variation spans the full range of $-\pi$ to $+\pi$ at each wavelength but varies weakly with the duty cycle due to the relatively low index of the glass grating. Higher-index materials such as [titanium dioxide](https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Titanium_dioxide#Thin_films) (TiO<sub>2</sub>) generally provide more control over the phase.

See [Tutorials/Near to Far Field Spectra/Focusing Properties of a Metasurface Lens](Near_to_Far_Field_Spectra.md#focusing-properties-of-a-metasurface-lens) for a related example.

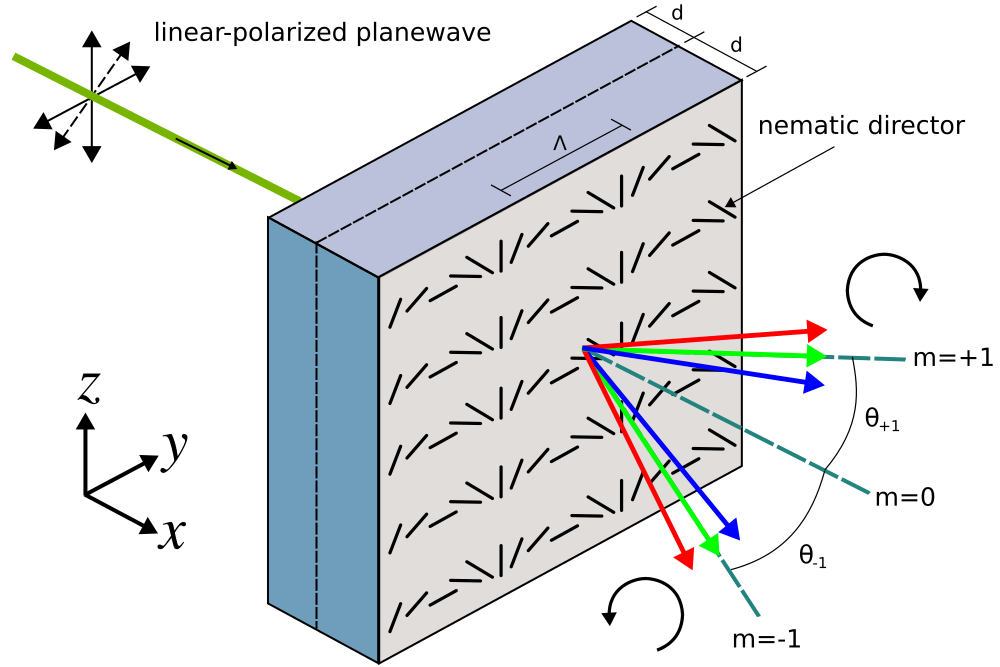

Diffraction Spectrum of Liquid-Crystal Polarization Gratings

------------------------------------------------------------

As a final demonstration of mode decomposition, we compute the diffraction spectrum of a [liquid-crystal](https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Liquid_crystal) polarization grating. These types of beam splitters use [birefringence](https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Birefringence) to produce diffraction orders which are [circularly polarized](https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Circular_polarization). We will investigate two kinds of polarization gratings: (1) a homogeneous [uniaxial](https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Birefringence#Uniaxial_materials) grating (commonly known as a circular-polarization grating), and (2) a [twisted-nematic](https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Liquid_crystal#Chiral_phases) bilayer grating as described in [Optics Letters, Vol. 33, No. 20, pp. 2287-9 (2008)](https://www.osapublishing.org/ol/abstract.cfm?uri=ol-33-20-2287) ([pdf](https://www.imagineoptix.com/cms/wp-content/uploads/2017/01/OL_08_Oh-broadband_PG.pdf)). The homogeneous uniaxial grating is just a special case of the twisted-nematic grating with a nematic [director](https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Liquid_crystal#Director) rotation angle of $\phi=0^{\circ}$.

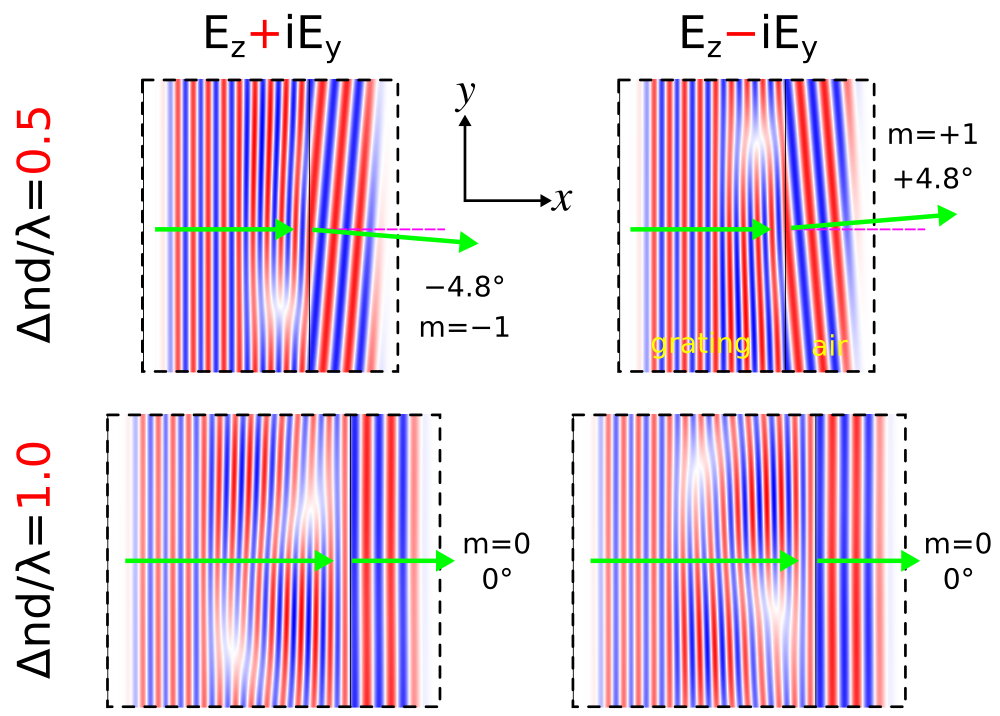

A schematic of the grating geometry is shown below. The grating is a 2d slab in the $xy$-plane with two parameters: birefringence ($\Delta n$) and thickness ($d$). The twisted-nematic grating consists of two layers of thickness $d$ each with equal and opposite rotation angles of $\phi = 70^{\circ}$ for the nematic director. Both gratings contain only three diffraction orders: $m = 0, \pm 1$. The $m=0$ order is linearly polarized and the $m=\pm 1$ orders are circularly polarized with opposite chirality. For the uniaxial grating, the diffraction efficiencies for a mode with wavelength $\lambda$ can be computed analytically: $\eta_0 = \cos^2(\pi\Delta n d/\lambda)$, $\eta_{\pm 1} = 0.5\sin^2(\pi\Delta n d/\lambda)$. The derivation of these formulas is presented in [Optics Letters, Vol. 24, No. 9, pp. 584-6 (1999)](https://www.osapublishing.org/ol/abstract.cfm?uri=ol-24-9-584). We will verify these analytic results and also demonstrate that the twisted-nematic grating produces a broader bandwidth response for the ±1 orders than the homogeneous uniaxial grating. An important property of these polarization gratings for e.g. display applications is that for a circular-polarized input planewave and phase delay ($\Delta n d/\lambda$) of nearly 0.5, there is only a single diffraction order (+1 or -1) with *opposite* chiraity to that of the input. This is also demonstrated below.

In this example, the input is a linear-polarized planewave pulse at normal incidence with center wavelength of $\lambda = 0.54$ μm. The linear polarization is in the $yz$-plane with a rotation angle of 45° counter clockwise around the $x$ axis. Two sets of mode coefficients are computed in the air region adjacent to the grating for each orthogonal polarization: `ODD_Z+EVEN_Y` and `EVEN_Z+ODD_Y`, which correspond to $+k_y + -k_y$ (cosine) and $+k_y - -k_y$ (sine) modes. From these coefficients for linear-polarized modes, the power in the circular-polarized modes can be computed: |ODD_Z+EVEN_Y|<sup>2</sup>+|EVEN_Z+ODD_Y|<sup>2</sup>. The power is identical for the two circular-polarized modes with opposite chiralities since the input is linearly polarized and at normal incidence. The transmittance for the diffraction orders are computed from the mode coefficients. Following usual practice, this requires a separate normalization run to compute the power of the input planewave.

The simulation script is in [examples/polarization_grating.py](https://github.com/NanoComp/meep/blob/master/python/examples/polarization_grating.py). The notebook is [examples/polarization_grating.ipynb](https://nbviewer.jupyter.org/github/NanoComp/meep/blob/master/python/examples/polarization_grating.ipynb).

The main part of the script is the function `pol_grating` which computes the mode coefficients for a grating with thickness `d`, twisted-nematic rotation angle `ph`, and periodicity `gp`. The anisotropic permittivity of the grating is specified using the [material function](../Python_User_Interface.md#medium) `lc_mat` which involves a position-dependent rotation of the diagonal $\varepsilon$ tensor about the $x$-axis. For $\phi = 0^{\circ}$, the nematic director is oriented along the $z$-axis: $E_z$ has a larger permittivity than $E_y$ where the birefringence ($\Delta n$) is 0.159. The grating has a periodicity of $\Lambda = 6.5$ μm in the $y$ direction.

```py

import meep as mp

import numpy as np

import math

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

resolution = 50 # pixels/μm

dpml = 1.0 # PML thickness

dsub = 1.0 # substrate thickness

dpad = 1.0 # padding thickness

k_point = mp.Vector3(0,0,0)

pml_layers = [mp.PML(thickness=dpml,direction=mp.X)]

n_0 = 1.55

delta_n = 0.159

epsilon_diag = mp.Matrix(mp.Vector3(n_0**2,0,0),mp.Vector3(0,n_0**2,0),mp.Vector3(0,0,(n_0+delta_n)**2))

wvl = 0.54 # center wavelength

fcen = 1/wvl # center frequency

def pol_grating(d,ph,gp,nmode):

sx = dpml+dsub+d+d+dpad+dpml

sy = gp

cell_size = mp.Vector3(sx,sy,0)

# twist angle of nematic director; from equation 1b

def phi(p):

xx = p.x-(-0.5*sx+dpml+dsub)

if (xx >= 0) and (xx <= d):

return math.pi*p.y/gp + ph*xx/d

else:

return math.pi*p.y/gp - ph*xx/d + 2*ph

# return the anisotropic permittivity tensor for a uniaxial, twisted nematic liquid crystal

def lc_mat(p):

# rotation matrix for rotation around x axis

Rx = mp.Matrix(mp.Vector3(1,0,0),mp.Vector3(0,math.cos(phi(p)),math.sin(phi(p))),mp.Vector3(0,-math.sin(phi(p)),math.cos(phi(p))))

lc_epsilon = Rx * epsilon_diag * Rx.transpose()

lc_epsilon_diag = mp.Vector3(lc_epsilon[0].x,lc_epsilon[1].y,lc_epsilon[2].z)

lc_epsilon_offdiag = mp.Vector3(lc_epsilon[1].x,lc_epsilon[2].x,lc_epsilon[2].y)

return mp.Medium(epsilon_diag=lc_epsilon_diag,epsilon_offdiag=lc_epsilon_offdiag)

geometry = [mp.Block(center=mp.Vector3(-0.5*sx+0.5*(dpml+dsub)),size=mp.Vector3(dpml+dsub,mp.inf,mp.inf),material=mp.Medium(index=n_0)),

mp.Block(center=mp.Vector3(-0.5*sx+dpml+dsub+d),size=mp.Vector3(2*d,mp.inf,mp.inf),material=lc_mat)]

# linear-polarized planewave pulse source

src_pt = mp.Vector3(-0.5*sx+dpml+0.3*dsub,0,0)

sources = [mp.Source(mp.GaussianSource(fcen,fwidth=0.05*fcen), component=mp.Ez, center=src_pt, size=mp.Vector3(0,sy,0)),

mp.Source(mp.GaussianSource(fcen,fwidth=0.05*fcen), component=mp.Ey, center=src_pt, size=mp.Vector3(0,sy,0))]

sim = mp.Simulation(resolution=resolution,

cell_size=cell_size,

boundary_layers=pml_layers,

k_point=k_point,

sources=sources,

default_material=mp.Medium(index=n_0))

tran_pt = mp.Vector3(0.5*sx-dpml-0.5*dpad,0,0)

tran_flux = sim.add_flux(fcen, 0, 1, mp.FluxRegion(center=tran_pt, size=mp.Vector3(0,sy,0)))

sim.run(until_after_sources=100)

input_flux = mp.get_fluxes(tran_flux)

sim.reset_meep()

sim = mp.Simulation(resolution=resolution,

cell_size=cell_size,

boundary_layers=pml_layers,

k_point=k_point,

sources=sources,

geometry=geometry)

tran_flux = sim.add_flux(fcen, 0, 1, mp.FluxRegion(center=tran_pt, size=mp.Vector3(0,sy,0)))

sim.run(until_after_sources=300)

res1 = sim.get_eigenmode_coefficients(tran_flux, range(1,nmode+1), eig_parity=mp.ODD_Z+mp.EVEN_Y)

res2 = sim.get_eigenmode_coefficients(tran_flux, range(1,nmode+1), eig_parity=mp.EVEN_Z+mp.ODD_Y)

angles = [math.degrees(math.acos(kdom.x/fcen)) for kdom in res1.kdom]

return input_flux[0], angles, res1.alpha[:,0,0], res2.alpha[:,0,0];

```

The properties of the two gratings are computed over a range of thicknesses from 0.1 to 3.4 μm corresponding to phase delays ($\Delta n d/\lambda$) of approximately 0 to 1.

```py

ph_uniaxial = 0 # chiral layer twist angle for uniaxial grating

ph_twisted = 70 # chiral layer twist angle for bilayer grating

gp = 6.5 # grating period

nmode = 5 # number of mode coefficients to compute

dd = np.arange(0.1,3.5,0.1) # chiral layer thickness

m0_uniaxial = np.zeros(dd.size)

m1_uniaxial = np.zeros(dd.size)

ang_uniaxial = np.zeros(dd.size)

m0_twisted = np.zeros(dd.size)

m1_twisted = np.zeros(dd.size)

ang_twisted = np.zeros(dd.size)

for k in range(len(dd)):

input_flux, angles, coeffs1, coeffs2 = pol_grating(0.5*dd[k],math.radians(ph_uniaxial),gp,nmode)

tran = (abs(coeffs1)**2+abs(coeffs2)**2)/input_flux

for m in range(nmode):

print("tran (uniaxial):, {}, {:.2f}, {:.5f}".format(m,angles[m],tran[m]))

m0_uniaxial[k] = tran[0]

m1_uniaxial[k] = tran[1]

ang_uniaxial[k] = angles[1]

input_flux, angles, coeffs1, coeffs2 = pol_grating(dd[k],math.radians(ph_twisted),gp,nmode)

tran = (abs(coeffs1)**2+abs(coeffs2)**2)/input_flux

for m in range(nmode):

print("tran (twisted):, {}, {:.2f}, {:.5f}".format(m,angles[m],tran[m]))

m0_twisted[k] = tran[0]

m1_twisted[k] = tran[1]

ang_twisted[k] = angles[1]

```

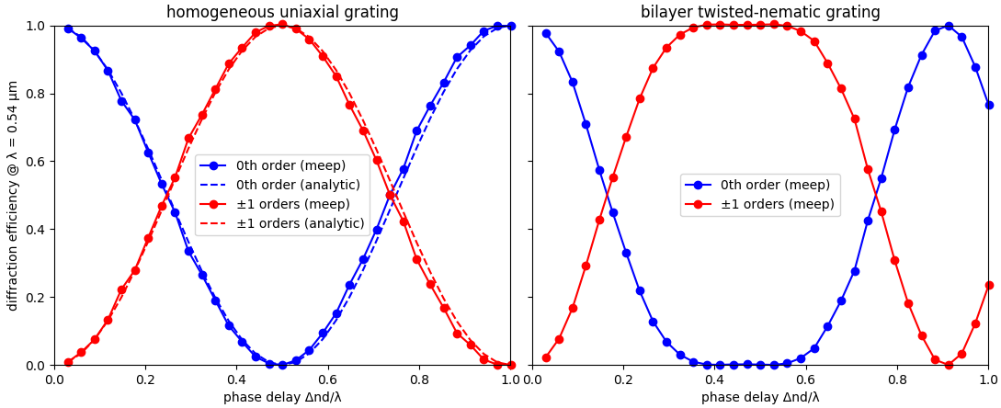

The diffraction spectra is plotted using the script below and shown in the accompanying figure.

```py

cos_angles = [math.cos(math.radians(t)) for t in ang_uniaxial]

tran = m0_uniaxial+2*m1_uniaxial

eff_m0 = m0_uniaxial/tran

eff_m1 = (2*m1_uniaxial/tran)/cos_angles

phase = delta_n*dd/wvl

eff_m0_analytic = [math.cos(math.pi*p)**2 for p in phase]

eff_m1_analytic = [math.sin(math.pi*p)**2 for p in phase]

plt.figure(dpi=150)

plt.subplot(1,2,1)

plt.plot(phase,eff_m0,'bo-',clip_on=False,label='0th order (meep)')

plt.plot(phase,eff_m0_analytic,'b--',clip_on=False,label='0th order (analytic)')

plt.plot(phase,eff_m1,'ro-',clip_on=False,label='±1 orders (meep)')

plt.plot(phase,eff_m1_analytic,'r--',clip_on=False,label='±1 orders (analytic)')

plt.axis([0, 1.0, 0, 1])

plt.xticks([t for t in np.arange(0,1.2,0.2)])

plt.xlabel("phase delay Δnd/λ")

plt.ylabel("diffraction efficiency @ λ = 0.54 μm")

plt.legend(loc='center')

plt.title("homogeneous uniaxial grating")

cos_angles = [math.cos(math.radians(t)) for t in ang_twisted]

tran = m0_twisted+2*m1_twisted

eff_m0 = m0_twisted/tran

eff_m1 = (2*m1_twisted/tran)/cos_angles

plt.subplot(1,2,2)

plt.plot(phase,eff_m0,'bo-',clip_on=False,label='0th order (meep)')

plt.plot(phase,eff_m1,'ro-',clip_on=False,label='±1 orders (meep)')

plt.axis([0, 1.0, 0, 1])

plt.xticks([t for t in np.arange(0,1.2,0.2)])

plt.xlabel("phase delay Δnd/λ")

plt.ylabel("diffraction efficiency @ λ = 0.54 μm")

plt.legend(loc='center')

plt.title("bilayer twisted-nematic grating")

plt.show()

```

The left figure shows good agreement between the simulation results and analytic theory for the homogeneous uniaxial grating. Approximately 6% of the power in the input planewave is lost due to reflection from the grating. This value is an average over all phase delays. The total transmittance is therefore around 94%. The twisted-nematic grating, with results shown in the right figure, produces ±1 diffraction orders with nearly-constant peak transmittance over a broader bandwidth around $\Delta nd/\lambda=0.5$ than the homogeneous uniaxial polarization grating. This is consistent with results from the reference. The average reflectance and transmittance for the twisted-nematic grating are similar to those for the homogeneous uniaxial grating.

Finally, we demonstrate that when $\Delta nd/\lambda=0.5$ a circular-polarized planewave input produces just a single ±1 diffraction order. To create a $\mathcal{J}_z + i\mathcal{J}_y$ circular-polarized planewave current source involves overlapping two linear-polarized planewave sources for $\mathcal{J}_y$ and $\mathcal{J}_z$ where the `amplitude` property of one of the sources is the imaginary number `1j` in order to create a phase offset of 90°:

```py

sources = [mp.Source(mp.GaussianSource(fcen,fwidth=0.05*fcen),

component=mp.Ez,

center=src_pt,

size=mp.Vector3(0,sy,0)),