1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

42

43

44

45

46

47

48

49

50

51

52

53

54

55

56

57

58

59

60

61

62

63

64

65

66

67

68

69

70

71

72

73

74

75

76

77

78

79

80

81

82

83

84

85

86

87

88

89

90

91

92

93

94

95

96

97

98

99

100

101

102

103

104

105

106

107

108

109

110

111

112

113

114

115

116

117

118

119

120

121

122

123

124

125

126

127

128

129

130

131

132

133

134

135

136

137

138

139

140

141

142

143

144

145

146

147

148

149

150

151

152

153

154

155

156

157

158

159

160

161

162

163

164

165

166

167

168

169

170

171

172

173

174

175

176

177

178

179

180

181

182

183

184

185

186

187

188

189

190

191

192

193

194

195

196

197

198

199

200

201

202

203

204

205

206

207

208

209

210

211

212

213

214

215

216

217

218

219

220

221

222

223

224

225

226

227

228

229

230

231

232

233

234

235

236

237

238

239

240

241

242

243

244

245

246

247

248

249

250

251

252

253

254

255

256

257

258

259

260

261

262

263

264

265

266

267

268

269

270

271

272

273

274

275

276

277

278

279

280

281

282

283

284

285

286

287

288

289

290

291

292

293

294

295

296

297

298

299

300

301

302

303

304

305

306

307

308

309

310

311

312

313

314

315

316

317

318

319

320

321

322

323

324

325

326

327

328

329

330

331

332

333

334

335

336

337

338

339

340

341

342

343

344

345

346

347

348

349

350

351

352

353

354

355

356

357

358

359

360

361

362

363

364

365

366

367

368

369

370

371

372

373

374

375

376

377

378

379

380

381

382

383

384

385

386

387

388

389

390

391

392

393

394

395

396

397

398

399

400

401

402

403

404

|

# Porting anisotropic image segmentation on G-API {#tutorial_gapi_anisotropic_segmentation}

@prev_tutorial{tutorial_gapi_interactive_face_detection}

@next_tutorial{tutorial_gapi_face_beautification}

[TOC]

# Introduction {#gapi_anisotropic_intro}

In this tutorial you will learn:

* How an existing algorithm can be transformed into a G-API

computation (graph);

* How to inspect and profile G-API graphs;

* How to customize graph execution without changing its code.

This tutorial is based on @ref

tutorial_anisotropic_image_segmentation_by_a_gst.

# Quick start: using OpenCV backend {#gapi_anisotropic_start}

Before we start, let's review the original algorithm implementation:

@include cpp/tutorial_code/ImgProc/anisotropic_image_segmentation/anisotropic_image_segmentation.cpp

## Examining calcGST() {#gapi_anisotropic_calcgst}

The function calcGST() is clearly an image processing pipeline:

* It is just a sequence of operations over a number of cv::Mat;

* No logic (conditionals) and loops involved in the code;

* All functions operate on 2D images (like cv::Sobel, cv::multiply,

cv::boxFilter, cv::sqrt, etc).

Considering the above, calcGST() is a great candidate to start

with. In the original code, its prototype is defined like this:

@snippet cpp/tutorial_code/ImgProc/anisotropic_image_segmentation/anisotropic_image_segmentation.cpp calcGST_proto

With G-API, we can define it as follows:

@snippet cpp/tutorial_code/gapi/porting_anisotropic_image_segmentation/porting_anisotropic_image_segmentation_gapi.cpp calcGST_proto

It is important to understand that the new G-API based version of

calcGST() will just produce a compute graph, in contrast to its

original version, which actually calculates the values. This is a

principal difference -- G-API based functions like this are used to

construct graphs, not to process the actual data.

Let's start implementing calcGST() with calculation of \f$J\f$

matrix. This is how the original code looks like:

@snippet cpp/tutorial_code/ImgProc/anisotropic_image_segmentation/anisotropic_image_segmentation.cpp calcJ_header

Here we need to declare output objects for every new operation (see

img as a result for cv::Mat::convertTo, imgDiffX and others as results for

cv::Sobel and cv::multiply).

The G-API analogue is listed below:

@snippet cpp/tutorial_code/gapi/porting_anisotropic_image_segmentation/porting_anisotropic_image_segmentation_gapi.cpp calcGST_header

This snippet demonstrates the following syntactic difference between

G-API and traditional OpenCV:

* All standard G-API functions are by default placed in "cv::gapi"

namespace;

* G-API operations _return_ its results -- there's no need to pass

extra "output" parameters to the functions.

Note -- this code is also using `auto` -- types of intermediate objects

like `img`, `imgDiffX`, and so on are inferred automatically by the

C++ compiler. In this example, the types are determined by G-API

operation return values which all are cv::GMat.

G-API standard kernels are trying to follow OpenCV API conventions

whenever possible -- so cv::gapi::sobel takes the same arguments as

cv::Sobel, cv::gapi::mul follows cv::multiply, and so on (except

having a return value).

The rest of calcGST() function can be implemented the same

way trivially. Below is its full source code:

@snippet cpp/tutorial_code/gapi/porting_anisotropic_image_segmentation/porting_anisotropic_image_segmentation_gapi.cpp calcGST

## Running G-API graph {#gapi_anisotropic_running}

After calcGST() is defined in G-API language, we can construct a graph

based on it and finally run it -- pass input image and obtain

result. Before we do it, let's have a look how original code looked

like:

@snippet cpp/tutorial_code/ImgProc/anisotropic_image_segmentation/anisotropic_image_segmentation.cpp main_extra

G-API-based functions like calcGST() can't be applied to input data

directly, since it is a _construction_ code, not the _processing_ code.

In order to _run_ computations, a special object of class

cv::GComputation needs to be created. This object wraps our G-API code

(which is a composition of G-API data and operations) into a callable

object, similar to C++11

[std::function<>](https://en.cppreference.com/w/cpp/utility/functional/function).

cv::GComputation class has a number of constructors which can be used

to define a graph. Generally, user needs to pass graph boundaries

-- _input_ and _output_ objects, on which a GComputation is

defined. Then G-API analyzes the call flow from _outputs_ to _inputs_

and reconstructs the graph with operations in-between the specified

boundaries. This may sound complex, however in fact the code looks

like this:

@snippet cpp/tutorial_code/gapi/porting_anisotropic_image_segmentation/porting_anisotropic_image_segmentation_gapi.cpp main

Note that this code slightly changes from the original one: forming up

the resulting image is also a part of the pipeline (done with

cv::gapi::addWeighted).

Result of this G-API pipeline bit-exact matches the original one

(given the same input image):

## G-API initial version: full listing {#gapi_anisotropic_ocv}

Below is the full listing of the initial anisotropic image

segmentation port on G-API:

@snippet cpp/tutorial_code/gapi/porting_anisotropic_image_segmentation/porting_anisotropic_image_segmentation_gapi.cpp full_sample

# Inspecting the initial version {#gapi_anisotropic_inspect}

After we have got the initial working version of our algorithm working

with G-API, we can use it to inspect and learn how G-API works. This

chapter covers two aspects: understanding the graph structure, and

memory profiling.

## Understanding the graph structure {#gapi_anisotropic_inspect_graph}

G-API stands for "Graph API", but did you mention any graphs in the

above example? It was one of the initial design goals -- G-API was

designed with expressions in mind to make adoption and porting process

more straightforward. People _usually_ don't think in terms of

_Nodes_ and _Edges_ when writing ordinary code, and so G-API, while

being a Graph API, doesn't force its users to do that.

However, a graph is still built implicitly when a cv::GComputation

object is defined. It may be useful to inspect how the resulting graph

looks like to check if it is generated correctly and if it really

represents our algorithm. It is also useful to learn the structure of

the graph to see if it has any redundancies.

G-API allows to dump generated graphs to `.dot` files which then

could be visualized with [Graphviz](https://www.graphviz.org/), a

popular open graph visualization software.

<!-- TODO THIS VARIABLE NEEDS TO BE FIXED TO DUMP DIR ASAP! -->

In order to dump our graph to a `.dot` file, set `GRAPH_DUMP_PATH` to a

file name before running the application, e.g.:

$ GRAPH_DUMP_PATH=segm.dot ./bin/example_tutorial_porting_anisotropic_image_segmentation_gapi

Now this file can be visualized with a `dot` command like this:

$ dot segm.dot -Tpng -o segm.png

or viewed interactively with `xdot` (please refer to your

distribution/operating system documentation on how to install these

packages).

The above diagram demonstrates a number of interesting aspects of

G-API's internal algorithm representation:

1. G-API underlying graph is a bipartite graph: it consists of

_Operation_ and _Data_ nodes such that a _Data_ node can only be

connected to an _Operation_ node, _Operation_ node can only be

connected to a _Data_ node, and nodes of a single kind are never

connected directly.

2. Graph is directed - every edge in the graph has a direction.

3. Graph "begins" and "ends" with a _Data_ kind of nodes.

4. A _Data_ node can have only a single writer and multiple readers.

5. An _Operation_ node may have multiple inputs, though every input

must have an unique _port number_ (among inputs).

6. An _Operation_ node may have multiple outputs, and every output

must have an unique _port number_ (among outputs).

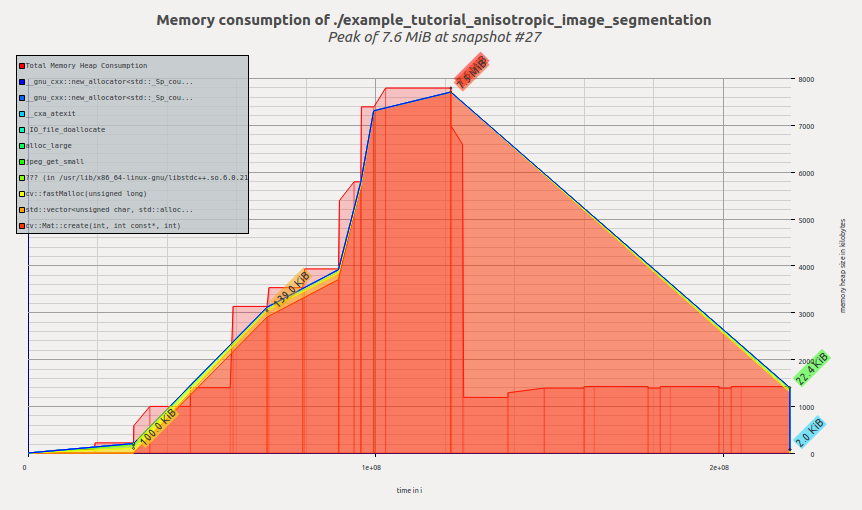

## Measuring memory footprint {#gapi_anisotropic_memory_ocv}

Let's measure and compare memory footprint of the algorithm in its two

versions: G-API-based and OpenCV-based. At the moment, G-API version

is also OpenCV-based since it fallbacks to OpenCV functions inside.

On GNU/Linux, application memory footprint can be profiled with

[Valgrind](http://valgrind.org/). On Debian/Ubuntu systems it can be

installed like this (assuming you have administrator privileges):

$ sudo apt-get install valgrind massif-visualizer

Once installed, we can collect memory profiles easily for our two

algorithm versions:

$ valgrind --tool=massif --massif-out-file=ocv.out ./bin/example_tutorial_anisotropic_image_segmentation

==6101== Massif, a heap profiler

==6101== Copyright (C) 2003-2015, and GNU GPL'd, by Nicholas Nethercote

==6101== Using Valgrind-3.11.0 and LibVEX; rerun with -h for copyright info

==6101== Command: ./bin/example_tutorial_anisotropic_image_segmentation

==6101==

==6101==

$ valgrind --tool=massif --massif-out-file=gapi.out ./bin/example_tutorial_porting_anisotropic_image_segmentation_gapi

==6117== Massif, a heap profiler

==6117== Copyright (C) 2003-2015, and GNU GPL'd, by Nicholas Nethercote

==6117== Using Valgrind-3.11.0 and LibVEX; rerun with -h for copyright info

==6117== Command: ./bin/example_tutorial_porting_anisotropic_image_segmentation_gapi

==6117==

==6117==

Once done, we can inspect the collected profiles with

[Massif Visualizer](https://github.com/KDE/massif-visualizer)

(installed in the above step).

Below is the visualized memory profile of the original OpenCV version

of the algorithm:

We see that memory is allocated as the application

executes, reaching its peak in the calcGST() function; then the

footprint drops as calcGST() completes its execution and all temporary

buffers are freed. Massif reports us peak memory consumption of 7.6 MiB.

Now let's have a look on the profile of G-API version:

Once G-API computation is created and its execution starts, G-API

allocates all required memory at once and then the memory profile

remains flat until the termination of the program. Massif reports us

peak memory consumption of 11.4 MiB.

A reader may ask a right question at this point -- is G-API that bad?

What is the reason in using it than?

Hopefully, it is not. The reason why we see here an increased memory

consumption is because the default naive OpenCV-based backend is used to

execute this graph. This backend serves mostly for quick prototyping

and debugging algorithms before offload/further optimization.

This backend doesn't utilize any complex memory management strategies yet

since it is not its point at the moment. In the following chapter,

we'll learn about Fluid backend and see how the same G-API code can

run in a completely different model (and the footprint shrunk to a

number of kilobytes).

# Backends and kernels {#gapi_anisotropic_backends}

This chapter covers how a G-API computation can be executed in a

special way -- e.g. offloaded to another device, or scheduled with a

special intelligence. G-API is designed to make its graphs portable --

it means that once a graph is defined in G-API terms, no changes

should be required in it if we want to run it on CPU or on GPU or on

both devices at once. [G-API High-level overview](@ref gapi_hld) and

[G-API Kernel API](@ref gapi_kernel_api) shed more light on technical

details which make it possible. In this chapter, we will utilize G-API

Fluid backend to make our graph cache-efficient on CPU.

G-API defines _backend_ as the lower-level entity which knows how to

run kernels. Backends may have (and, in fact, do have) different

_Kernel APIs_ which are used to program and integrate kernels for that

backends. In this context, _kernel_ is an implementation of an

_operation_, which is defined on the top API level (see

G_TYPED_KERNEL() macro).

Backend is a thing which is aware of device & platform specifics, and

which executes its kernels with keeping that specifics in mind. For

example, there may be [Halide](http://halide-lang.org/) backend which

allows to write (implement) G-API operations in Halide language and

then generate functional Halide code for portions of G-API graph which

map well there.

## Running a graph with a Fluid backend {#gapi_anisotropic_fluid}

OpenCV 4.0 is bundled with two G-API backends -- the default "OpenCV"

which we just used, and a special "Fluid" backend.

Fluid backend reorganizes the execution to save memory and to achieve

near-perfect cache locality, implementing so-called "streaming" model

of execution.

In order to start using Fluid kernels, we need first to include

appropriate header files (which are not included by default):

@snippet cpp/tutorial_code/gapi/porting_anisotropic_image_segmentation/porting_anisotropic_image_segmentation_gapi_fluid.cpp fluid_includes

Once these headers are included, we can form up a new _kernel package_

and specify it to G-API:

@snippet cpp/tutorial_code/gapi/porting_anisotropic_image_segmentation/porting_anisotropic_image_segmentation_gapi_fluid.cpp kernel_pkg

In G-API, kernels (or operation implementations) are objects. Kernels are

organized into collections, or _kernel packages_, represented by class

cv::GKernelPackage. The main purpose of a kernel package is to

capture which kernels we would like to use in our graph, and pass it

as a _graph compilation option_:

@snippet cpp/tutorial_code/gapi/porting_anisotropic_image_segmentation/porting_anisotropic_image_segmentation_gapi_fluid.cpp kernel_pkg_use

Traditional OpenCV is logically divided into modules, with every

module providing a set of functions. In G-API, there are also

"modules" which are represented as kernel packages provided by a

particular backend. In this example, we pass Fluid kernel packages to

G-API to utilize appropriate Fluid functions in our graph.

Kernel packages are combinable -- in the above example, we take "Core"

and "ImgProc" Fluid kernel packages and combine it into a single

one. See documentation reference on cv::gapi::combine.

If no kernel packages are specified in options, G-API is using

_default_ package which consists of default OpenCV implementations and

thus G-API graphs are executed via OpenCV functions by default. OpenCV

backend provides broader functional coverage than any other

backend. If a kernel package is specified, like in this example, then

it is being combined with the _default_.

It means that user-specified implementations will replace default implementations in case of

conflict.

<!-- FIXME Document this process better as a part of regular -->

<!-- documentation, not a tutorial kind of thing -->

## Troubleshooting and customization {#gapi_anisotropic_trouble}

After the above modifications, (in OpenCV 4.0) the app should crash

with a message like this:

```

$ ./bin/example_tutorial_porting_anisotropic_image_segmentation_gapi_fluid

terminate called after throwing an instance of 'std::logic_error'

what(): .../modules/gapi/src/backends/fluid/gfluidimgproc.cpp:436: Assertion kernelSize.width == 3 && kernelSize.height == 3 in function run failed

Aborted (core dumped)

```

Fluid backend has a number of limitations in OpenCV 4.0 (see this

[wiki page](https://github.com/opencv/opencv/wiki/Graph-API) for a

more up-to-date status). In particular, the Box filter used in this

sample supports only static 3x3 kernel size.

We can overcome this problem easily by avoiding G-API using Fluid

version of Box filter kernel in this sample. It can be done by

removing the appropriate kernel from the kernel package we've just

created:

@snippet cpp/tutorial_code/gapi/porting_anisotropic_image_segmentation/porting_anisotropic_image_segmentation_gapi_fluid.cpp kernel_hotfix

Now this kernel package doesn't have _any_ implementation of Box

filter kernel interface (specified as a template parameter). As

described above, G-API will fall-back to OpenCV to run this kernel

now. The resulting code with this change now looks like:

@snippet cpp/tutorial_code/gapi/porting_anisotropic_image_segmentation/porting_anisotropic_image_segmentation_gapi_fluid.cpp kernel_pkg_proper

Let's examine the memory profile for this sample after we switched to

Fluid backend. Now it looks like this:

Now the tool reports 4.7MiB -- and we just changed a few lines in our

code, without modifying the graph itself! It is a ~2.4X improvement of

the previous G-API result, and ~1.6X improvement of the original OpenCV

version.

Let's also examine how the internal representation of the graph now

looks like. Dumping the graph into `.dot` would result into a

visualization like this:

This graph doesn't differ structurally from its previous version (in

terms of operations and data objects), though a changed layout (on the

left side of the dump) is easily noticeable.

The visualization reflects how G-API deals with mixed graphs, also

called _heterogeneous_ graphs. The majority of operations in this

graph are implemented with Fluid backend, but Box filters are executed

by the OpenCV backend. One can easily see that the graph is partitioned

(with rectangles). G-API groups connected operations based on their

affinity, forming _subgraphs_ (or _islands_ in G-API terminology), and

our top-level graph becomes a composition of multiple smaller

subgraphs. Every backend determines how its subgraph (island) is

executed, so Fluid backend optimizes out memory where possible, and

six intermediate buffers accessed by OpenCV Box filters are allocated

fully and can't be optimized out.

<!-- TODO: add a chapter on custom kernels -->

<!-- TODO: make a full-fluid pipeline -->

<!-- TODO: talk about parallelism when it is available -->

# Conclusion {#gapi_tutor_conclusion}

This tutorial demonstrates what G-API is and what its key design

concepts are, how an algorithm can be ported to G-API, and

how to utilize graph model benefits after that.

In OpenCV 4.0, G-API is still in its inception stage -- it is more a

foundation for all future work, though ready for use even now.

Further, this tutorial will be extended with new chapters on custom

kernels programming, parallelism, and more.

|