1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

42

43

44

45

46

47

48

49

50

51

52

53

54

55

56

57

58

59

60

61

62

63

64

65

66

67

68

69

70

71

72

73

74

75

76

77

78

79

80

81

82

83

84

85

86

87

88

89

90

91

92

93

94

95

96

97

98

99

100

101

102

103

104

105

106

107

108

109

110

111

112

113

114

115

116

117

118

119

120

121

122

123

124

125

126

127

128

129

130

131

132

133

134

135

136

137

138

139

140

141

142

143

144

145

146

147

148

149

150

151

152

153

154

155

156

157

158

159

160

161

162

163

164

165

166

167

168

169

170

171

172

173

174

175

176

177

178

179

180

181

182

183

184

185

186

187

188

189

190

191

192

193

194

195

196

197

198

199

200

201

|

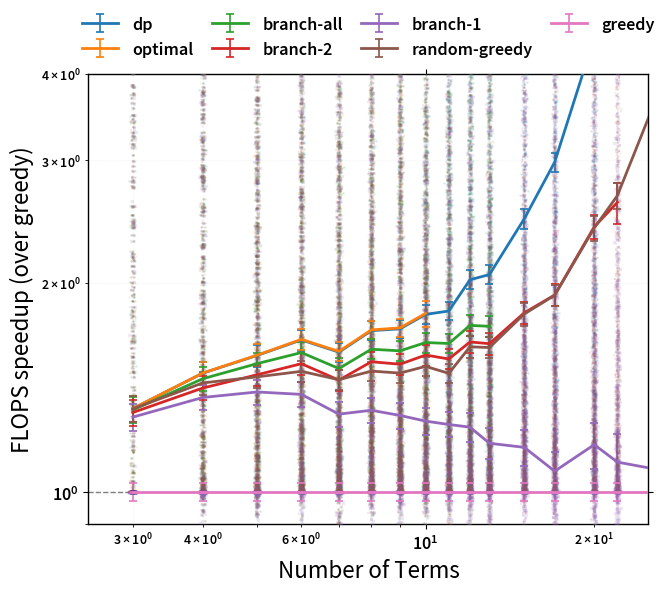

# Introduction

Performing an optimized tensor contraction to speed up `einsum` involves two

key stages:

1. Finding a pairwise contraction order, or **'path'**.

2. Performing the sequence of contractions given this path.

The better the quality of path found in the first step, the quicker the actual

contraction in the second step can be -- often dramatically. However, finding

the *optimal* path is an NP-hard problem that can quickly become intractable,

meaning that a balance must be struck between the time spent finding a path,

and its quality. `opt_einsum` handles this by using several path finding

algorithms, which can be manually specified using the `optimize` keyword.

These are:

- The `'optimal'` strategy - an exhaustive search of all possible paths

- The `'dynamic-programming'` strategy - a near-optimal search based off dynamic-programming

- The `'branch'` strategy - a more restricted search of many likely paths

- The `'greedy'` strategy - finds a path one step at a time using a cost

heuristic

By default (`optimize='auto'`), [`opt_einsum.contract`](../api_reference.md#opt_einsumcontract) will select the

best of these it can while aiming to keep path finding times below around 1ms.

An analysis of each of these approaches' performance can be found at the bottom of this page.

For large and complex contractions, there is the `'random-greedy'` approach,

which samples many (by default 32) greedy paths and can be customized to

explicitly spend a maximum amount of time searching. Another preset,

`'random-greedy-128'`, uses 128 paths for a more exhaustive search.

See [`RandomGreedyPath`](./random_greedy_path.md) page for more details on configuring these.

Finally, there is the `'auto-hq'` preset which targets a much larger search

time (~1sec) in return for finding very high quality paths, dispatching to the

`'optimal'`, `'dynamic-programming'` and then `'random-greedy-128'` paths

depending on contraction size.

If you want to find the path separately to performing the

contraction, or just inspect information about the path found, you can use the

function [`opt_einsum.contract_path`](../api_reference.md#opt_einsumcontract_path).

## Examining the Path

As an example, consider the following expression found in a perturbation theory (one of ~5,000 such expressions):

```python

'bdik,acaj,ikab,ajac,ikbd'

```

At first, it would appear that this scales like N^7 as there are 7 unique indices; however, we can define a intermediate to reduce this scaling.

```python

# (N^5 scaling)

a = 'bdik,ikab,ikbd'

# (N^4 scaling)

result = 'acaj,ajac,a'

```

This is a single possible path to the final answer (and notably, not the most optimal) out of many possible paths. Now, let opt_einsum compute the optimal path:

```python

import opt_einsum as oe

# Take a complex string

einsum_string = 'bdik,acaj,ikab,ajac,ikbd->'

# Build random views to represent this contraction

unique_inds = set(einsum_string) - {',', '-', '>'}

index_size = [10, 17, 9, 10, 13, 16, 15, 14, 12]

sizes_dict = dict(zip(unique_inds, index_size))

views = oe.helpers.build_views(einsum_string, sizes_dict)

path, path_info = oe.contract_path(einsum_string, *views)

print(path)

#> [(0, 4), (1, 3), (0, 1), (0, 1)]

print(path_info)

#> Complete contraction: bdik,acaj,ikab,ajac,ikbd->

#> Naive scaling: 7

#> Optimized scaling: 4

#> Naive FLOP count: 2.387e+8

#> Optimized FLOP count: 8.068e+4

#> Theoretical speedup: 2958.354

#> Largest intermediate: 1.530e+3 elements

#> --------------------------------------------------------------------------------

#> scaling BLAS current remaining

#> --------------------------------------------------------------------------------

#> 4 0 ikbd,bdik->ikb acaj,ikab,ajac,ikb->

#> 4 GEMV/EINSUM ikb,ikab->a acaj,ajac,a->

#> 3 0 ajac,acaj->a a,a->

#> 1 DOT a,a-> ->

```

We can then check that actually performing the contraction produces the expected result:

```python

import numpy as np

einsum_result = np.einsum("bdik,acaj,ikab,ajac,ikbd->", *views)

contract_result = oe.contract("bdik,acaj,ikab,ajac,ikbd->", *views)

np.allclose(einsum_result, contract_result)

#> True

```

By contracting terms in the correct order we can see that this expression can be computed with N^4 scaling. Even with the overhead of finding the best order or 'path' and small dimensions,

`opt_einsum` is roughly 3000 times faster than pure einsum for this expression.

## Format of the Path

Let us look at the structure of a canonical `einsum` path found in NumPy and its optimized variant:

```python

einsum_path = [(0, 1, 2, 3, 4)]

opt_path = [(1, 3), (0, 2), (0, 2), (0, 1)]

```

In opt_einsum each element of the list represents a single contraction.

In the above example the einsum_path would effectively compute the result as a single contraction identical to that of `einsum`, while the

opt_path would perform four contractions in order to reduce the overall scaling.

The first tuple in the opt_path, `(1,3)`, pops the second and fourth terms, then contracts them together to produce a new term which is then appended to the list of terms, this is continued until all terms are contracted.

An example should illuminate this:

```console

---------------------------------------------------------------------------------

scaling GEMM current remaining

---------------------------------------------------------------------------------

terms = ['bdik', 'acaj', 'ikab', 'ajac', 'ikbd'] contraction = (1, 3)

3 False ajac,acaj->a bdik,ikab,ikbd,a->

terms = ['bdik', 'ikab', 'ikbd', 'a'] contraction = (0, 2)

4 False ikbd,bdik->bik ikab,a,bik->

terms = ['ikab', 'a', 'bik'] contraction = (0, 2)

4 False bik,ikab->a a,a->

terms = ['a', 'a'] contraction = (0, 1)

1 DOT a,a-> ->

```

A path specified in this format can explicitly be supplied directly to

[`opt_einsum.contract`](../api_reference.md#opt_einsumcontract) using the `optimize` keyword:

```python

contract_result = oe.contract("bdik,acaj,ikab,ajac,ikbd->", *views, optimize=opt_path)

np.allclose(einsum_result, contract_result)

#> True

```

## Performance Comparison

The following graphs should give some indication of the tradeoffs between path

finding time and path quality. They are generated by finding paths with each

possible algorithm for many randomly generated networks of `n` tensors with

varying connectivity.

First we have the time to find each path as a function of the number of terms

in the expression:

Clearly the exhaustive (`'optimal'`, `'branch-all'`) and exponential

(`'branch-2'`) searches eventually scale badly, but for modest amounts of

terms they incur only a small overhead. The `'random-greedy'` approach is not

shown here as it is simply `max_repeats` times slower than the `'greedy'`

approach - at least if not parallelized.

Next we can look at the average FLOP speedup (as compared to the easiest path

to find, `'greedy'`):

One can see that the hierarchy of path qualities is:

1. `'optimal'` (used by auto for `n <= 4`)

2. `'branch-all'` (used by auto for `n <= 6`)

3. `'branch-2'` (used by auto for `n <= 8`)

4. `'branch-1'` (used by auto for `n <= 14`)

5. `'greedy'` (used by auto for anything larger)

!!! note

The performance of the `'random=greedy'` approach (which is never used

automatically) can be found separately in [`RandomGreedyPath`](./random_greedy_path.md) section.

There are a few important caveats to note with this graph. Firstly, the

benefits of more advanced path finding are very dependent on the complexity of

the expression. For 'simple' contractions, all the different approaches will

*mostly* find the same path (as here). However, for 'tricky' contractions, there

will be certain cases where the more advanced algorithms will find much better

paths. As such, while this graph gives a good idea of the *relative* performance

of each algorithm, the 'average speedup' is not a perfect indicator since

worst-case performance might be more critical.

Note that the speedups for any of the methods as compared to a standard

`einsum` or a naively chosen path (such as `path=[(0, 1), (0, 1), ...]`)

are all exponentially large and not shown.

|