1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

42

43

44

45

46

47

48

49

50

51

52

53

54

55

56

57

58

59

60

61

62

63

64

65

66

67

68

69

70

71

72

73

74

75

76

77

78

79

80

81

82

83

84

85

86

87

88

89

90

91

92

93

94

95

96

97

98

99

100

101

102

103

104

105

106

107

108

109

110

111

112

113

114

115

116

117

118

119

120

121

122

123

124

125

126

127

128

129

130

131

132

133

134

135

136

137

138

139

140

141

142

143

144

145

146

147

148

149

150

151

152

153

154

155

156

157

158

159

160

161

162

163

164

165

166

167

168

169

170

171

172

173

174

175

176

177

178

179

180

181

|

# More on Dependency Resolution

This article goes into more detail about pip's dependency resolution algorithm.

In certain situations, pip can take a long time to determine what to install,

and this article is intended to help readers understand what is happening

"behind the scenes" during that process.

```{note}

This document is a work in progress. The details included are accurate (at the

time of writing), but there is additional information, in particular around

pip's interface with resolvelib, which has not yet been included.

Contributions to improve this document are welcome.

```

## The dependency resolution problem

The process of finding a set of packages to install, given a set of dependencies

between them, is known to be an [NP-hard](https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/NP-hardness)

problem. What this means in practice is roughly that the process scales

*extremely* badly as the size of the problem increases. So when you have a lot

of dependencies, working out what to install will, in the worst case, take a

very long time.

The practical implication of that is that there will always be some situations

where pip cannot determine what to install in a reasonable length of time. We

make every effort to ensure that such situations happen rarely, but eliminating

them altogether isn't even theoretically possible. We'll discuss what options

you have if you hit a problem situation like this a little later.

## Python specific issues

Many algorithms for handling dependency resolution assume that you know the

full details of the problem at the start - that is, you know all of the

dependencies up front. Unfortunately, that is not the case for Python packages.

With the current package index structure, dependency metadata is only available

by downloading the package file, and extracting the data from it. And in the

case of source distributions, the situation is even worse as the project must

be built after being downloaded in order to determine the dependencies.

Work is ongoing to try to make metadata more readily available at lower cost,

but at the time of writing, this has not been completed.

As downloading projects is a costly operation, pip cannot pre-compute the full

dependency tree. This means that we are unable to use a number of techniques

for solving the dependency resolution problem. In practice, we have to use a

*backtracking algorithm*.

## Dependency metadata

It is worth discussing precisely what metadata is needed in order to drive the

package resolution process. There are essentially three key pieces of

information:

* The project name

* The release version

* The dependencies themselves

There are other pieces of data (e.g., extras, python version restrictions, wheel

compatibility tags) which are used as well, but they do not fundamentally

alter the process, so we will ignore them here.

The most important information is the project name and version. Those two pieces

of information identify an individual "candidate" for installation, and must

uniquely identify such a candidate. Name and version must be available from the

moment the candidate object is created. This is not an issue for distribution

files (sdists and wheels) as that data is available from the filename, but for

unpackaged source trees, pip needs to call the build backend to ask for that

data. This is done before resolution proper starts.

The dependency data is *not* requested in advance (as noted above, doing so

would be prohibitively costly, and for a backtracking algorithm it isn't

needed). Instead, pip requests dependency data "on demand", as the algorithm

starts to check that particular candidate.

One particular implication of the lazy fetching of dependency data is that

often, pip *does not know* things that might be obvious to a human looking at

the dependency tree as a whole. For example, if package A depends on version

1.0 of package B, it's obvious to a human that there's no point in looking at

other versions of package B. But if pip starts looking at B before it has

considered A, it doesn't have access to A's dependency data, and so has no way

of knowing that looking at other versions of B is wasted work. And worse still,

pip cannot even know that there's vital information in A's dependencies.

This latter point is a common theme with many cases where pip takes a long time

to complete a resolution - there's information pip doesn't know at the point

where it makes a "wrong" choice. Most of the heuristics added to the resolver

to guide the algorithm are designed to guess correctly in the face of that

lack of knowledge.

## The resolver and the finder

So far, we have been talking about the "resolver" as a single entity. While that

is mostly true, the process of getting package data from an index is handled

by another component of pip, the "finder". The finder is responsible for

feeding candidates to the resolver, and has a key role to play in selecting

suitable candidates.

Note that the resolver is *only* relevant for packages fetched from an index.

Candidates coming from other sources (local source directories, {ref}`direct

URL references <pypug:dependency-specifiers>`) do *not* go through the finder,

and are merged with the candidates provided by the finder as part of the resolver's

"provider" implementation.

As well as determining what versions exist in the index for a given project,

the finder selects the best distribution file to use for that candidate. This

may be a wheel or a source distribution, and precisely what is selected is

controlled by wheel compatibility tags, pip's options (whether to prefer binary

or source) and metadata supplied by the index. In particular, if a file is

marked as only being for specific Python versions, the file will be ignored by

the finder (and the resolver may never even see that version).

The finder also provides candidates for a project to the resolver in order of

preference - the provider implements the rule that later versions are preferred

over older versions, for example.

## The resolver algorithm

The resolver itself is based on a separate package, [resolvelib](https://pypi.org/project/resolvelib/).

This implements an abstract backtracking resolution algorithm, in a way that is

independent of the specifics of Python packages - those specifics are abstracted

away by pip before calling the resolver.

Pip's interface to resolvelib is in the form of a "provider", which is the

interface between pip's model of packages and the resolution algorithm. The

provider deals in "candidates" and "requirements" and implements the following

operations:

* `identify` - implements identity for candidates and requirements. It is this

operation that implements the rule that candidates are identified by their

name and version, for example.

* `get_preference` - this provides information to the resolver to help it choose

which requirement to look at "next" when working through the resolution

process.

* `narrow_requirement_selection` - this provides a way to limit the number of

identifiers passed to `get_preference`.

* `find_matches` - given a set of constraints, determine what candidates exist

that satisfy them. This is essentially where the finder interacts with the

resolver.

* `is_satisfied_by` - checks if a candidate satisfies a requirement. This is

basically the implementation of what a requirement means.

* `get_dependencies` - get the dependency metadata for a candidate. This is

the implementation of the process of getting and reading package metadata.

Of these methods, the only non-trivial ones are the `get_preference` and

`narrow_requirement_selection` methods. These implement heuristics used

to guide the resolution, telling it which requirement to try to satisfy next.

It's these methods that are responsible for trying to guess which route through

the dependency tree will be most productive. As noted above, it's doing this

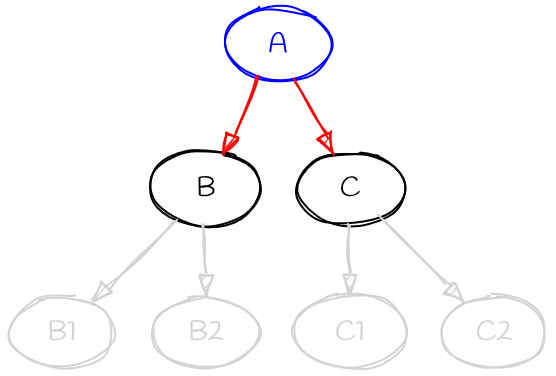

with limited information. See the following diagram:

When the provider is asked to choose between the red requirements (A->B and

A->C) it doesn't know anything about the dependencies of B or C (i.e., the

grey parts of the graph).

Pip's current implementation of the provider implements

`narrow_requirement_selection` as follows:

* If Requires-Python is present only consider that

* If there are causes of resolution conflict (backtrack causes) then

only consider them until there are no longer any resolution conflicts

Pip's current implementation of the provider implements `get_preference`

for known requirements with the following preferences in the following order:

* Any requirement that is "direct", e.g., points to an explicit URL.

* Any requirement that is "pinned", i.e., contains the operator ``===``

or ``==`` without a wildcard.

* Any requirement that imposes an upper version limit, i.e., contains the

operator ``<``, ``<=``, ``~=``, or ``==`` with a wildcard. Because

pip prioritizes the latest version, preferring explicit upper bounds

can rule out infeasible candidates sooner. This does not imply that

upper bounds are good practice; they can make dependency management

and resolution harder.

* Order user-specified requirements as they are specified, placing

other requirements afterward.

* Any "non-free" requirement, i.e., one that contains at least one

operator, such as ``>=`` or ``!=``.

* Alphabetical order for consistency (aids debuggability).

|