1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

42

43

44

45

46

47

48

49

50

51

52

53

54

55

56

57

58

59

60

61

62

63

64

65

66

67

68

69

70

71

72

73

74

75

76

77

78

79

80

81

82

83

84

85

86

87

88

89

90

91

92

93

94

95

96

97

98

99

100

101

102

103

104

105

106

107

108

109

110

111

112

113

114

115

116

117

118

119

120

121

122

123

124

125

126

127

128

129

130

131

132

133

134

135

136

137

138

139

140

141

142

143

144

145

146

147

148

149

150

151

152

153

154

155

156

157

158

159

160

161

162

163

164

165

166

167

168

169

170

171

172

173

174

175

176

177

178

179

180

181

182

183

184

185

186

187

188

189

190

191

192

193

194

195

196

197

198

199

200

201

202

203

204

205

206

207

208

209

210

211

212

213

214

215

216

217

218

219

220

221

222

223

224

225

226

227

228

229

230

231

232

233

234

235

236

237

238

239

240

241

242

243

244

245

246

247

248

249

250

251

252

253

254

255

256

257

258

259

260

261

262

263

264

265

266

267

268

269

270

271

272

273

274

275

276

277

278

279

280

281

282

283

284

285

286

287

288

289

290

291

292

293

294

295

296

297

298

299

300

301

302

303

304

305

306

307

308

309

310

311

312

313

314

315

316

317

318

319

320

321

322

323

324

325

326

327

328

329

330

331

332

333

334

335

336

337

338

339

340

341

342

343

344

345

346

347

348

349

350

351

352

353

354

355

356

357

358

359

360

361

362

363

364

365

366

367

368

369

370

371

372

373

374

375

376

377

378

379

380

381

382

383

384

385

386

387

388

389

390

391

392

393

394

395

396

397

398

399

400

401

402

403

404

405

406

407

408

409

410

411

412

413

414

415

416

417

418

419

420

421

422

423

424

425

426

427

428

429

430

431

432

433

434

435

436

437

438

439

440

441

442

443

444

445

446

447

448

449

450

451

452

453

454

455

456

457

458

459

460

461

462

463

464

465

466

467

468

469

470

471

472

473

474

475

476

477

478

479

480

481

482

483

484

485

486

487

488

489

490

491

492

493

494

495

496

497

498

|

---

title: "An Introduction to merTools"

author: "Jared Knowles and Carl Frederick"

date: "2020-06-22"

output: rmarkdown::html_vignette

vignette: >

%\VignetteEngine{knitr::rmarkdown}

%\VignetteIndexEntry{An Introduction to merTools}

%\VignetteEncoding{UTF-8}

---

## Introduction

Working with generalized linear mixed models (GLMM) and linear mixed models (LMM)

has become increasingly easy with the advances in the `lme4` package recently.

As we have found ourselves using these models more and more within our work, we,

the authors, have developed a set of tools for simplifying and speeding up common

tasks for interacting with `merMod` objects from `lme4`. This package provides

those tools.

## Illustrating Model Effects

As the complexity of the model fit grows, it becomes harder and harder to

interpret the substantive effect of parameters in the model.

Let's start with a medium-sized example model using the `InstEval` data provided

by the `lme4` package. These data represent university lecture evaluations at

ETH Zurich made by students. In this data, `s` is an individual student,

`d` is an individual lecturer, `studage` is the semester the student

is enrolled, `lectage` is how many semesters back the lecture with the

rating took place, `dept` is the department of the lecture, and `y` is an integer

1:5 representing the ratings of the lecture from "poor" to "very good":

```r

library(lme4)

head(InstEval)

#> s d studage lectage service dept y

#> 1 1 1002 2 2 0 2 5

#> 2 1 1050 2 1 1 6 2

#> 3 1 1582 2 2 0 2 5

#> 4 1 2050 2 2 1 3 3

#> 5 2 115 2 1 0 5 2

#> 6 2 756 2 1 0 5 4

str(InstEval)

#> 'data.frame': 73421 obs. of 7 variables:

#> $ s : Factor w/ 2972 levels "1","2","3","4",..: 1 1 1 1 2 2 3 3 3 3 ...

#> $ d : Factor w/ 1128 levels "1","6","7","8",..: 525 560 832 1068 62 406 3 6 19 75 ...

#> $ studage: Ord.factor w/ 4 levels "2"<"4"<"6"<"8": 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 ...

#> $ lectage: Ord.factor w/ 6 levels "1"<"2"<"3"<"4"<..: 2 1 2 2 1 1 1 1 1 1 ...

#> $ service: Factor w/ 2 levels "0","1": 1 2 1 2 1 1 2 1 1 1 ...

#> $ dept : Factor w/ 14 levels "15","5","10",..: 14 5 14 12 2 2 13 3 3 3 ...

#> $ y : int 5 2 5 3 2 4 4 5 5 4 ...

```

Starting with a simple model:

```r

m1 <- lmer(y ~ service + lectage + studage + (1|d) + (1|s), data=InstEval)

```

After fitting the model we can make use of the first function provided by

`merTools`, `fastdisp` which modifies the function `arm:::display` to more

quickly display a summary of the model without calculating the model sigma:

```r

library(merTools)

fastdisp(m1)

#> lmer(formula = y ~ service + lectage + studage + (1 | d) + (1 |

#> s), data = InstEval)

#> coef.est coef.se

#> (Intercept) 3.22 0.02

#> service1 -0.07 0.01

#> lectage.L -0.19 0.02

#> lectage.Q 0.02 0.01

#> lectage.C -0.02 0.01

#> lectage^4 -0.02 0.01

#> lectage^5 -0.04 0.02

#> studage.L 0.10 0.02

#> studage.Q 0.01 0.02

#> studage.C 0.02 0.02

#>

#> Error terms:

#> Groups Name Std.Dev.

#> s (Intercept) 0.33

#> d (Intercept) 0.52

#> Residual 1.18

#> ---

#> number of obs: 73421, groups: s, 2972; d, 1128

#> AIC = 237655

```

We see some interesting effects. First, our decision to include student and

lecturer effects seems justified as there is substantial variance within these

groups. Second, there do appear to be some effects by age and for lectures

given as a service by an outside lecturer. Let's look at these in more detail.

One way to do this would be to plot the coefficients together in a line to

see which deviate from 0 and in what direction. To get a confidence interval

for our fixed effect coefficients we have a number of options that represent a

tradeoff between coverage and computation time -- see `confint.merMod` for

details.

An alternative is to simulate values of the fixed effects from the posterior

using the function `arm::sim`. Our next tool, `FEsim`, is a convenience wrapper

to do this and provide an informative data frame of the results.

```r

feEx <- FEsim(m1, 1000)

cbind(feEx[,1] , round(feEx[, 2:4], 3))

#> feEx[, 1] mean median sd

#> 1 (Intercept) 3.225 3.225 0.020

#> 2 service1 -0.070 -0.070 0.013

#> 3 lectage.L -0.186 -0.186 0.017

#> 4 lectage.Q 0.024 0.024 0.012

#> 5 lectage.C -0.025 -0.025 0.013

#> 6 lectage^4 -0.020 -0.019 0.014

#> 7 lectage^5 -0.039 -0.039 0.015

#> 8 studage.L 0.096 0.096 0.018

#> 9 studage.Q 0.005 0.005 0.017

#> 10 studage.C 0.017 0.017 0.016

```

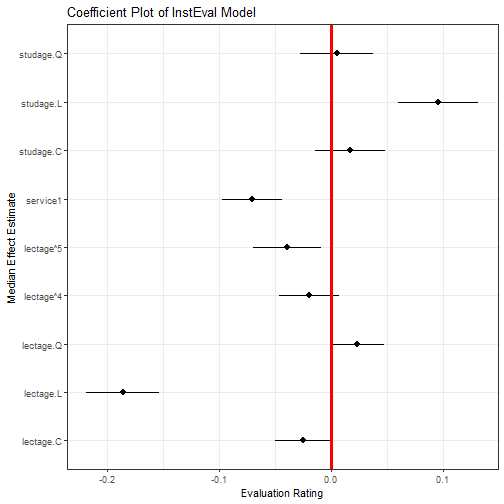

We can present these results graphically, using `ggplot2`:

```r

library(ggplot2)

ggplot(feEx[feEx$term!= "(Intercept)", ]) +

aes(x = term, ymin = median - 1.96 * sd,

ymax = median + 1.96 * sd, y = median) +

geom_pointrange() +

geom_hline(yintercept = 0, size = I(1.1), color = I("red")) +

coord_flip() +

theme_bw() + labs(title = "Coefficient Plot of InstEval Model",

x = "Median Effect Estimate", y = "Evaluation Rating")

```

However, an easier option is:

```r

plotFEsim(feEx) +

theme_bw() + labs(title = "Coefficient Plot of InstEval Model",

x = "Median Effect Estimate", y = "Evaluation Rating")

```

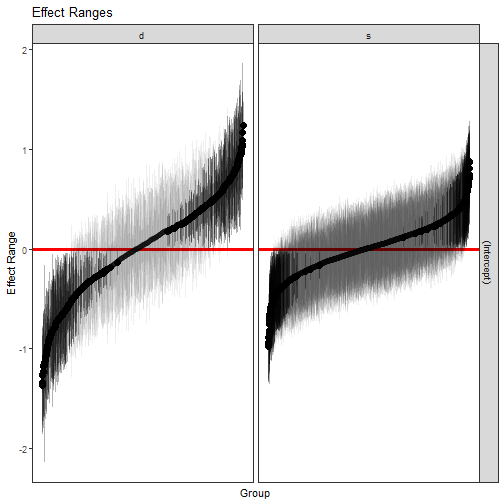

## Random Effects

Next, we might be interested in exploring the random effects. Again, we create a

dataframe of the values of the simulation of these effects for the individual

levels.

```r

reEx <- REsim(m1)

head(reEx)

#> groupFctr groupID term mean median sd

#> 1 s 1 (Intercept) 0.18042888 0.21906223 0.3145710

#> 2 s 2 (Intercept) -0.07034954 -0.06339508 0.2972897

#> 3 s 3 (Intercept) 0.32105622 0.33625741 0.3187445

#> 4 s 4 (Intercept) 0.23713963 0.23271723 0.2761635

#> 5 s 5 (Intercept) 0.02613185 0.02878794 0.3054642

#> 6 s 6 (Intercept) 0.10806580 0.11082677 0.2429651

```

The result is a dataframe with estimates of the values of each of the random

effects provided by the `arm::sim()` function. *groupID* represents the identfiable

level for the variable for one random effect, *term* represents whether the

simulated values are for an intercept or which slope, and *groupFctr* identifies

which of the `(1|x)` terms the values represent. To make unique identifiers

for each term, we need to use both the `groupID` and the `groupFctr` term in case

these two variables use overlapping label names for their groups. In this case:

```r

table(reEx$term)

#>

#> (Intercept)

#> 4100

table(reEx$groupFctr)

#>

#> d s

#> 1128 2972

```

Most important is producing caterpillar or dotplots of these terms to explore

their variation. This is easily accomplished with the `dotplot` function:

```r

lattice::dotplot(ranef(m1, condVar=TRUE))

```

However, these graphics do not provide much control over the results. Instead,

we can use the `plotREsim` function in `merTools` to gain more control over

plotting of the random effect simulations.

```r

p1 <- plotREsim(reEx)

p1

```

The result is a ggplot2 object which can be modified however the user sees

fit. Here, we've established that most student and professor effects are

indistinguishable from zero, but there do exist extreme outliers with both

high and low averages that need to be accounted for.

## Subtantive Effects

A logical next line of questioning is to see how much of the variation in a

rating can be caused by changing the student rater and how much is due to the

fixed effects we identified above. This is a very difficult problem to solve,

but using simulation we can examine the model behavior under a range of scenarios

to understand how the model is reflecting changes in the data. To do this,

we use another set of functions available in `merTools`.

The simplest option is to pick an observation at random and then modify its

values deliberately to see how the prediction changes in response. `merTools`

makes this task very simple:

```r

example1 <- draw(m1, type = 'random')

head(example1)

#> y service lectage studage d s

#> 29762 1 0 1 4 403 1208

```

The `draw` function takes a random observation from the data in the model

and extracts it as a dataframe. We can now do a number of operations to this

observation:

```r

# predict it

predict(m1, newdata = example1)

#> 29762

#> 3.742122

# change values

example1$service <- "1"

predict(m1, newdata = example1)

#> 29762

#> 3.671278

```

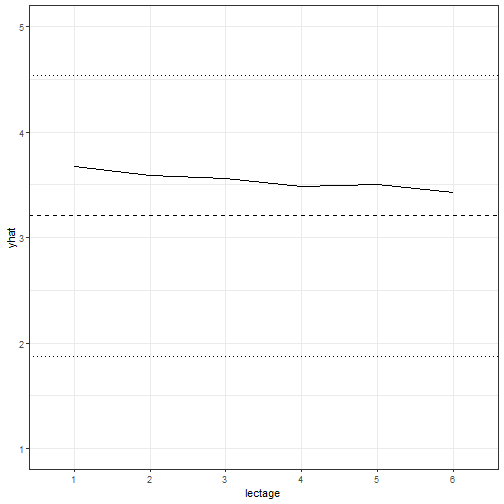

More interesting, let's programatically modify this observation to see how the

predicted value changes if we hold everything but one variable constant.

```r

example2 <- wiggle(example1, varlist = "lectage",

valueslist = list(c("1", "2", "3", "4", "5", "6")))

example2

#> y service lectage studage d s

#> 29762 1 1 1 4 403 1208

#> 297621 1 1 2 4 403 1208

#> 297622 1 1 3 4 403 1208

#> 297623 1 1 4 4 403 1208

#> 297624 1 1 5 4 403 1208

#> 297625 1 1 6 4 403 1208

```

The function `wiggle` allows us to create a new dataframe with copies of the

variable that modify just one value. Chaining together `wiggle` calls, we

can see how the variable behaves under a number of different scenarios

simultaneously.

```r

example2$yhat <- predict(m1, newdata = example2)

ggplot(example2, aes(x = lectage, y = yhat)) + geom_line(aes(group = 1)) +

theme_bw() + ylim(c(1, 5)) +

geom_hline(yintercept = mean(InstEval$y), linetype = 2) +

geom_hline(yintercept = mean(InstEval$y) + sd(InstEval$y), linetype = 3) +

geom_hline(yintercept = mean(InstEval$y) - sd(InstEval$y), linetype = 3)

```

The result allows us to graphically display the effect of each level of `lectage`

on an observation that is otherwise identical. This is plotted here against a

horizontal line representing the mean of the observed ratings, and two finer

lines showing plus or minus one standard deviation of the mean.

This is nice, but selecting a random observation is not very satisfying as it

may not be very meaningful. To address this, we can instead take the average

observation:

```r

example3 <- draw(m1, type = 'average')

example3

#> y service lectage studage d s

#> 1 3.205745 0 1 6 1510 2237

```

Here, the average observation is identified based on either the modal observation

for factors or on the mean for numeric variables. Then, the random effect

terms are set to the level equivalent to the median effect -- very close

to 0.

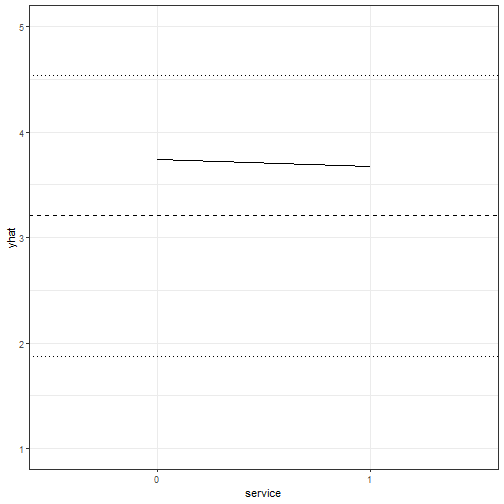

```r

example3 <- wiggle(example1, varlist = "service",

valueslist = list(c("0", "1")))

example3$yhat <- predict(m1, newdata = example3)

ggplot(example3, aes(x = service, y = yhat)) + geom_line(aes(group = 1)) +

theme_bw() + ylim(c(1, 5)) +

geom_hline(yintercept = mean(InstEval$y), linetype = 2) +

geom_hline(yintercept = mean(InstEval$y) + sd(InstEval$y), linetype = 3) +

geom_hline(yintercept = mean(InstEval$y) - sd(InstEval$y), linetype = 3)

```

Here we can see that for the average observation, whether the lecture is outside

of the home department has a very slight negative effect on the overall rating.

Might the individual professor or student have more of an impact on the overall

rating? To answer this question we need to wiggle the same observation across

a wide range of student or lecturer effects.

How do we identify this range? `merTools` provides the `REquantile` function

which helps to identify which levels of the grouping terms correspond to which

quantile of the magnitude of the random effects:

```r

REquantile(m1, quantile = 0.25, groupFctr = "s")

#> [1] "446"

REquantile(m1, quantile = 0.25, groupFctr = "d")

#> [1] "18"

```

Here we can see that group level 446

corresponds to the 25th percentile of the effect for the student groups, and level

`REquantile(m1, quantile = 0.25, groupFctr = "d")` corresponds to the 25th

percentile for the instructor group. Using this information we can reassign

a specific observation to varying magnitudes of grouping term effects to see

how much they might influence our final prediction.

```r

example4 <- draw(m1, type = 'average')

example4 <- wiggle(example4, varlist = "s",

list(REquantile(m1, quantile = seq(0.1, 0.9, .1),

groupFctr = "s")))

example4$yhat <- predict(m1, newdata = example4)

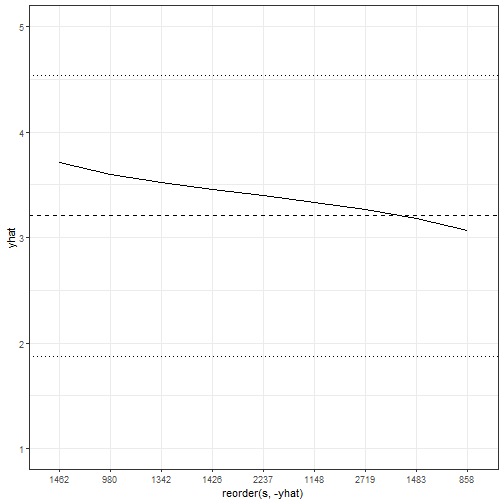

ggplot(example4, aes(x = reorder(s, -yhat), y = yhat)) +

geom_line(aes(group = 1)) +

theme_bw() + ylim(c(1, 5)) +

geom_hline(yintercept = mean(InstEval$y), linetype = 2) +

geom_hline(yintercept = mean(InstEval$y) + sd(InstEval$y), linetype = 3) +

geom_hline(yintercept = mean(InstEval$y) - sd(InstEval$y), linetype = 3)

```

This figure is very interesting because it shows that moving across the range

of student effects can have a larger impact on the score than the fixed effects

we observed above. That is, getting a "generous" or a "stingy" rater can have

a substantial impact on the final rating.

But, we can do even better. First, we can move beyond the average observation

by taking advantage of the `varList` option to the function which allows us to

specify a subset of the data to compute an average for.

```r

subExample <- list(studage = "2", lectage = "4")

example5 <- draw(m1, type = 'average', varList = subExample)

example5

#> y service lectage studage d s

#> 1 3.087193 0 4 2 1510 2237

```

Now we have the average observation with a student age of 2 and a lecture age

of 4. We can then follow the same procedure as before to explore the effects

on our subsamples. Before we do that, let's fit a slightly more complex model

that includes a random slope.

```r

data(VerbAgg)

m2 <- glmer(r2 ~ Anger + Gender + btype + situ +

(1|id) + (1 + Gender|item), family = binomial,

data = VerbAgg)

example6 <- draw(m2, type = 'average', varList = list("id" = "149"))

example6$btype <- "scold"

example6$situ <- "self"

tempdf <- wiggle(example6, varlist = "Gender", list(c("M", "F")))

tempdf <- wiggle(tempdf, varlist = "item",

list(unique(VerbAgg$item)))

tempdf$yhat <- predict(m2, newdata = tempdf, type = "response",

allow.new.levels = TRUE)

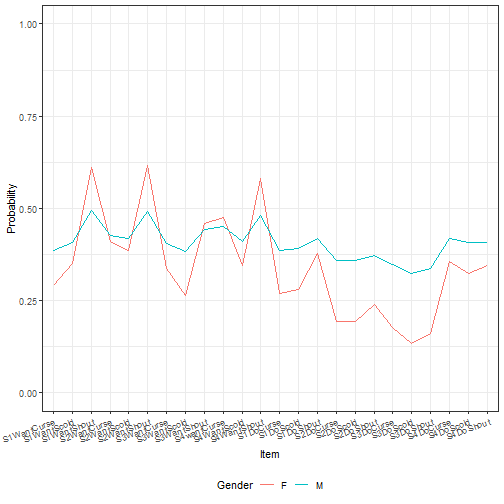

ggplot(tempdf, aes(x = item, y = yhat, group = Gender)) +

geom_line(aes(color = Gender))+

theme_bw() + ylim(c(0, 1)) +

theme(axis.text.x = element_text(angle = 20, hjust=1),

legend.position = "bottom") + labs(x = "Item", y = "Probability")

```

Here we've shown that the effect of both the intercept and the gender slope on

item simultaneously affect our predicted value. This results in the two lines

for predicted values across the items not being parallel. While we can see this

by looking at the results of the summary of the model object, using `fastdisp`

in the `merTools` package for larger models, it is not intuitive what that

effect looks like across different scenarios. `merTools` has given us the

machinery to investigate this.

## Uncertainty

The above examples make use of simulation to show the model behavior after

changing some values in a dataset. However, until now, we've focused on using

point estimates to represent these changes. The use of predicted point estimates

without incorporating any uncertainty can lead to overconfidence in the precision

of the model.

In the `predictInterval` function, discussed in more detail in another package

vignette, we provide a way to incorporate three out of the four types of

uncertainty inherent in a model. These are:

1. Overall model uncertainty

2. Uncertainty in fixed effect values

3. Uncertainty in random effect values

4. Uncertainty in the distribution of the random effects

1-3 are incorporated in the results of `predictInterval`, while capturing 4

would require making use of the `bootMer` function -- options discussed in

greater detail elsewhere. The main advantage of `predictInterval` is that it is

fast. By leveraging the power of the `arm::sim()` function, we are able to

generate prediction intervals for individual observations from very large models

very quickly. And, it works a lot like `predict`:

```r

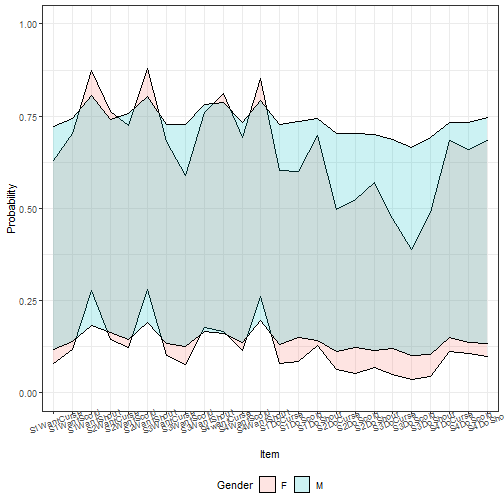

exampPreds <- predictInterval(m2, newdata = tempdf,

type = "probability", level = 0.8)

tempdf <- cbind(tempdf, exampPreds)

ggplot(tempdf, aes(x = item, y = fit, ymin = lwr, ymax = upr,

group = Gender)) +

geom_ribbon(aes(fill = Gender), alpha = I(0.2), color = I("black"))+

theme_bw() + ylim(c(0, 1)) +

theme(axis.text.x = element_text(angle = 20),

legend.position = "bottom")+ labs(x = "Item", y = "Probability")

```

Here we can see there is barely any gender difference in terms of area of

potential prediction intervals. However, by default, this approach includes the

residual variance of the model. If we instead focus just on the uncertainty of

the random and fixed effects, we get:

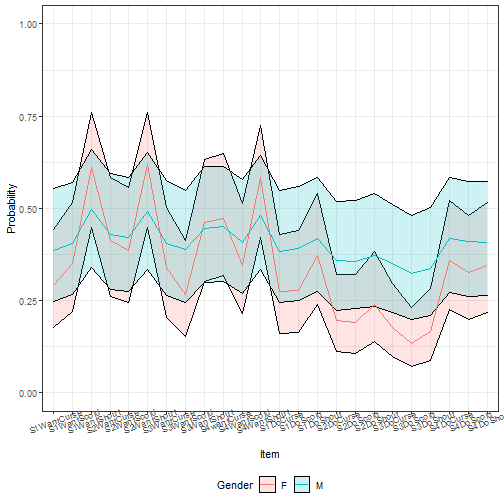

```r

exampPreds <- predictInterval(m2, newdata = tempdf,

type = "probability",

include.resid.var = FALSE, level = 0.8)

tempdf <- cbind(tempdf[, 1:8], exampPreds)

ggplot(tempdf, aes(x = item, y = fit, ymin = lwr, ymax = upr,

group = Gender)) +

geom_ribbon(aes(fill = Gender), alpha = I(0.2), color = I("black"))+

geom_line(aes(color = Gender)) +

theme_bw() + ylim(c(0, 1)) +

theme(axis.text.x = element_text(angle = 20),

legend.position = "bottom") + labs(x = "Item", y = "Probability")

```

Here, more difference emerges, but we see that the differences are not very

precise.

|