1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

42

43

44

45

46

47

48

49

50

51

52

53

54

55

56

57

58

59

60

61

62

63

64

65

66

67

68

69

70

71

72

73

74

75

76

77

78

79

80

81

82

83

84

85

86

87

88

89

90

91

92

93

94

95

96

97

98

99

100

101

102

103

104

105

106

107

108

109

110

111

112

113

114

115

116

117

118

119

120

121

122

123

124

125

126

127

128

129

130

131

132

133

134

135

136

137

138

139

140

141

142

143

144

145

146

147

148

149

150

151

152

153

154

155

156

157

158

159

160

161

162

163

164

165

166

167

168

169

170

171

172

173

174

175

176

177

178

179

180

181

182

183

184

185

186

187

188

189

190

191

192

193

194

195

196

197

198

199

200

201

202

203

204

205

206

207

208

209

210

211

212

213

214

215

216

217

218

219

220

221

222

223

224

225

226

227

228

229

230

231

232

233

234

235

236

237

238

239

240

241

242

243

244

245

246

247

248

249

250

251

252

253

254

255

256

257

258

259

260

261

262

263

264

265

266

267

268

269

270

271

272

273

274

275

276

277

278

279

280

281

282

283

284

285

286

287

288

289

290

291

292

293

294

295

296

297

298

299

300

301

302

303

304

305

306

307

308

309

310

311

312

313

314

315

316

317

318

319

320

321

322

323

324

325

326

327

328

329

330

331

332

333

334

335

336

337

338

339

340

341

342

343

344

345

346

347

348

349

350

351

352

353

354

355

356

357

358

359

360

361

362

363

364

365

366

367

368

369

370

371

372

373

374

375

376

377

378

379

380

381

382

383

384

385

386

387

388

389

390

391

392

393

394

395

396

397

398

399

400

401

402

403

404

405

406

407

408

409

410

411

412

413

414

415

416

417

418

419

420

421

422

423

424

425

426

427

428

429

430

431

432

433

434

435

436

437

438

439

440

441

442

443

444

445

446

447

448

449

450

451

452

453

454

455

456

457

458

459

460

461

462

463

464

465

466

467

468

469

470

471

472

473

474

475

476

477

478

479

480

481

482

483

484

485

486

487

488

489

490

491

492

493

494

495

496

497

498

499

500

501

502

503

504

505

506

507

508

509

510

511

512

513

514

515

516

517

518

519

520

521

522

523

524

525

526

527

528

529

530

531

532

533

534

535

536

537

538

539

540

541

542

543

544

545

546

547

548

549

550

551

552

553

554

555

556

557

558

559

560

561

562

563

564

565

566

567

568

569

570

571

572

573

574

575

576

577

578

579

580

581

582

583

584

585

586

587

588

589

590

591

592

593

594

595

596

597

598

599

600

601

602

603

604

605

606

607

608

609

610

611

612

613

614

615

616

617

618

619

620

621

622

623

624

625

626

627

628

629

630

631

632

633

634

635

636

637

638

639

640

641

642

643

644

645

646

647

648

649

650

651

652

653

654

655

656

657

658

659

660

661

662

663

664

665

666

667

668

669

670

671

672

673

674

675

676

677

678

679

680

681

682

683

684

685

686

687

688

689

690

691

692

693

694

695

696

697

698

699

700

701

702

703

704

705

706

707

708

709

710

711

712

713

714

715

716

717

718

719

720

721

722

723

724

725

726

727

728

729

730

731

732

733

734

735

736

737

738

739

740

741

742

743

744

745

746

747

748

749

750

751

752

753

754

755

756

757

758

759

760

761

762

763

764

765

766

767

768

769

770

771

772

773

774

775

776

777

778

779

780

781

782

783

784

785

786

787

788

789

790

791

792

793

794

795

796

797

798

799

800

801

802

803

804

805

806

807

808

809

810

811

812

813

814

815

816

817

818

819

820

821

822

823

824

825

826

827

828

829

830

831

832

833

834

835

836

837

838

839

840

841

842

843

844

845

846

847

848

849

850

851

852

853

854

855

856

857

858

859

860

861

862

863

864

865

866

867

868

869

870

871

872

873

874

875

876

877

878

879

880

881

882

883

884

885

886

887

888

889

890

891

892

893

894

895

896

897

898

899

900

901

902

903

904

905

906

907

908

909

910

911

912

913

914

915

916

917

918

919

920

921

922

923

924

925

926

927

928

929

930

931

932

933

934

935

936

937

938

939

940

941

942

943

944

945

946

947

948

949

950

951

952

953

954

955

956

957

958

959

960

961

962

963

964

965

966

967

968

969

970

971

972

973

974

975

976

977

978

979

980

981

982

983

984

985

986

987

988

989

990

991

992

993

994

995

996

997

998

999

1000

1001

1002

1003

1004

1005

1006

1007

1008

1009

1010

1011

1012

1013

1014

1015

1016

1017

1018

1019

1020

1021

1022

1023

1024

1025

1026

1027

1028

1029

1030

1031

1032

1033

1034

1035

1036

1037

1038

1039

1040

1041

1042

1043

1044

1045

1046

1047

1048

1049

1050

1051

1052

1053

1054

1055

1056

1057

1058

1059

1060

1061

1062

1063

1064

1065

1066

1067

1068

1069

1070

1071

1072

1073

1074

1075

1076

1077

1078

1079

1080

1081

1082

1083

1084

1085

1086

1087

1088

1089

1090

1091

1092

1093

1094

1095

1096

1097

1098

1099

1100

1101

1102

1103

1104

1105

1106

1107

1108

1109

1110

1111

1112

1113

1114

1115

1116

1117

1118

1119

1120

1121

1122

1123

1124

1125

1126

1127

1128

1129

1130

1131

1132

1133

1134

1135

1136

1137

1138

1139

1140

1141

1142

1143

1144

1145

1146

1147

1148

1149

1150

1151

1152

1153

1154

1155

1156

1157

1158

1159

1160

1161

1162

1163

1164

1165

1166

1167

1168

1169

1170

1171

1172

1173

1174

1175

1176

1177

1178

1179

1180

1181

1182

1183

1184

1185

1186

1187

1188

1189

1190

1191

1192

1193

1194

1195

1196

1197

1198

1199

1200

1201

1202

1203

1204

1205

1206

1207

1208

1209

1210

1211

1212

1213

1214

1215

1216

1217

1218

1219

1220

1221

1222

1223

1224

1225

1226

1227

1228

|

---

title: "Working with RabbitMQ exchanges and publishing messages from Ruby with Bunny"

layout: article

---

## About this guide

This guide covers the use of exchanges according to the AMQP 0.9.1

specification, including broader topics related to message publishing,

common usage scenarios and how to accomplish typical operations using

Bunny.

This work is licensed under a <a rel="license"

href="http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/">Creative Commons

Attribution 3.0 Unported License</a> (including images and

stylesheets). The source is available [on

GitHub](https://github.com/ruby-amqp/rubybunny.info).

## What version of Bunny does this guide cover?

This guide covers Bunny 2.11.0 and later versions.

## Exchanges in AMQP 0.9.1 — Overview

### What are AMQP exchanges?

An *exchange* accepts messages from a producer application and routes

them to message queues. They can be thought of as the "mailboxes" of

the AMQP world. Unlike some other messaging middleware products and

protocols, in AMQP, messages are *not* published directly to queues.

Messages are published to exchanges that route them to queue(s) using

pre-arranged criteria called *bindings*.

There are multiple exchange types in the AMQP 0.9.1 specification,

each with its own routing semantics. Custom exchange types can be

created to deal with sophisticated routing scenarios (e.g. routing

based on geolocation data or edge cases) or just for convenience.

### Concept of Bindings

A *binding* is an association between a queue and an exchange. A queue

must be bound to at least one exchange in order to receive messages

from publishers. Learn more about bindings in the [Bindings

guide](/articles/bindings.html).

### Exchange attributes

Exchanges have several attributes associated with them:

* Name

* Type (direct, fanout, topic, headers or some custom type)

* Durability

* Whether the exchange is auto-deleted when no longer used

* Other metadata (sometimes known as *X-arguments*)

## Exchange types

There are four built-in exchange types in AMQP v0.9.1:

* Direct

* Fanout

* Topic

* Headers

As stated previously, each exchange type has its own routing semantics

and new exchange types can be added by extending brokers with

plugins. Custom exchange types begin with "x-", much like custom HTTP

headers, e.g. [x-consistent-hash

exchange](https://github.com/rabbitmq/rabbitmq-consistent-hash-exchange)

or [x-random exchange](https://github.com/jbrisbin/random-exchange).

## Message attributes

Before we start looking at various exchange types and their routing

semantics, we need to introduce message attributes. Every AMQP message

has a number of *attributes*. Some attributes are important and used

very often, others are rarely used. AMQP message attributes are

metadata and are similar in purpose to HTTP request and response

headers.

Every AMQP 0.9.1 message has an attribute called *routing key*. The

routing key is an "address" that the exchange may use to decide how to

route the message. This is similar to, but more generic than, a URL in

HTTP. Most exchange types use the routing key to implement routing

logic, but some ignore it and use other criteria (e.g. message

content).

## Fanout exchanges

### How fanout exchanges route messages

A fanout exchange routes messages to all of the queues that are bound

to it and the routing key is ignored. If N queues are bound to a

fanout exchange, when a new message is published to that exchange a

*copy of the message* is delivered to all N queues. Fanout exchanges

are ideal for the [broadcast

routing](http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Broadcasting_%28computing%29) of

messages.

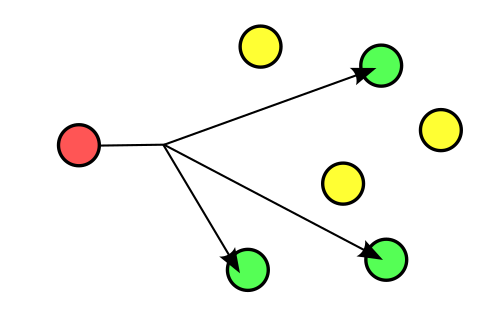

Graphically this can be represented as:

### Declaring a fanout exchange

There are two ways to declare a fanout exchange:

* Using the `Bunny::Channel#fanout` method

* Instantiate `Bunny::Exchange` directly

Here are two examples to demonstrate:

``` ruby

require "bunny"

conn = Bunny.new

conn.start

ch = conn.create_channel

x = ch.fanout("activity.events")

```

``` ruby

require "bunny"

conn = Bunny.new

conn.start

ch = conn.create_channel

x = Bunny::Exchange.new(ch, :fanout, "activity.events")

```

### Fanout routing example

To demonstrate fanout routing behavior we can declare ten server-named

exclusive queues, bind them all to one fanout exchange and then

publish a message to the exchange:

``` ruby

#!/usr/bin/env ruby

# encoding: utf-8

require "rubygems"

require "bunny"

puts "=> Fanout exchange routing"

puts

conn = Bunny.new

conn.start

ch = conn.create_channel

x = ch.fanout("examples.pings")

10.times do |i|

q = ch.queue("", :auto_delete => true).bind(x)

q.subscribe do |delivery_info, properties, payload|

puts "[consumer] #{q.name} received a message: #{payload}"

end

end

x.publish("Ping")

sleep 0.5

x.delete

puts "Disconnecting..."

conn.close

```

When run, this example produces the following output:

<pre>

=> Fanout exchange routing

[consumer] amq.gen-A8z-tj-n_0U39GdPGncV-A received a message: Ping

[consumer] amq.gen-jht-OtRwdD8LuHMxrA5SNQ received a message: Ping

[consumer] amq.gen-LQTh8IdojOCrvOnEuFog8w received a message: Ping

[consumer] amq.gen-PV-Dg8_gSvLO9eK6le6wwQ received a message: Ping

[consumer] amq.gen-ofAMc3FXRZIj3O55fXDSwA received a message: Ping

[consumer] amq.gen-TXJiZEjwZ0squ12_Z9mP0A received a message: Ping

[consumer] amq.gen-XQjh2xrC9khbMZMg_0Zzfw received a message: Ping

[consumer] amq.gen-XVSKsdWwhyxRiJn-jAFEGg received a message: Ping

[consumer] amq.gen-ZaY2pD_9NaOICxAMWPoIYw received a message: Ping

[consumer] amq.gen-oElfvP_crgASWkk6EhrJLA received a message: Ping

Disconnecting...

</pre>

Each of the queues bound to the exchange receives a *copy* of the

message.

### Fanout use cases

Because a fanout exchange delivers a copy of a message to every queue bound to it, its use cases are quite similar:

* Massively multiplayer online (MMO) games can use it for leaderboard updates or other global events

* Sport news sites can use fanout exchanges for distributing score updates to mobile clients in near real-time

* Distributed systems can broadcast various state and configuration updates

* Group chats can distribute messages between participants using a fanout exchange (although AMQP does not have a built-in concept of presence, so [XMPP](http://xmpp.org) may be a better choice)

### Pre-declared fanout exchanges

AMQP 0.9.1 brokers must implement a fanout exchange type and

pre-declare one instance with the name of `"amq.fanout"`.

Applications can rely on that exchange always being available to

them. Each vhost has a separate instance of that exchange, it is *not

shared across vhosts* for obvious reasons.

## Direct exchanges

### How direct exchanges route messages

A direct exchange delivers messages to queues based on a *message

routing key*, an attribute that every AMQP v0.9.1 message contains.

Here is how it works:

* A queue binds to the exchange with a routing key K

* When a new message with routing key R arrives at the direct exchange, the exchange routes it to the queue if K = R

A direct exchange is ideal for the [unicast

routing](http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Unicast) of messages (although

they can be used for [multicast

routing](http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Multicast) as well).

Here is a graphical representation:

### Declaring a direct exchange

* Using the `Bunny::Channel#direct` method

* Instantiate `Bunny::Exchange` directly

Here are two examples to demonstrate:

``` ruby

require "bunny"

conn = Bunny.new

conn.start

ch = conn.create_channel

x = ch.direct("imaging")

```

``` ruby

require "bunny"

conn = Bunny.new

conn.start

ch = conn.create_channel

x = Bunny::Exchange.new(ch, :direct, "imaging")

```

### Direct routing example

Since direct exchanges use the *message routing key* for routing,

message producers need to specify it:

``` ruby

#!/usr/bin/env ruby

# encoding: utf-8

require "rubygems"

require "bunny"

puts "=> Direct exchange routing"

puts

conn = Bunny.new

conn.start

ch = conn.create_channel

x = ch.direct("examples.imaging")

q1 = ch.queue("", :auto_delete => true).bind(x, :routing_key => "resize")

q1.subscribe do |delivery_info, properties, payload|

puts "[consumer] #{q1.name} received a 'resize' message"

end

q2 = ch.queue("", :auto_delete => true).bind(x, :routing_key => "watermark")

q2.subscribe do |delivery_info, properties, payload|

puts "[consumer] #{q2.name} received a 'watermark' message"

end

# just an example

data = rand.to_s

x.publish(data, :routing_key => "resize")

x.publish(data, :routing_key => "watermark")

sleep 0.5

x.delete

q1.delete

q2.delete

puts "Disconnecting..."

conn.close

```

The routing key will then be compared for equality with routing keys

on bindings, and consumers that subscribed with the same routing key

each get a copy of the message.

Output for the example looks like this:

```

=> Direct exchange routing

[consumer] amq.gen-8XIeaBCmykwnJUtHVEkT5Q received a 'resize' message

[consumer] amq.gen-Zht5YW3_MhK-YBLZouxp5Q received a 'watermark' message

Disconnecting...

```

### Direct Exchanges and Load Balancing of Messages

Direct exchanges are often used to distribute tasks between multiple

workers (instances of the same application) in a round robin manner.

When doing so, it is important to understand that, in AMQP 0.9.1,

*messages are load balanced between consumers and not between queues*.

The [Queues and Consumers](/articles/queues.html) guide provides more

information on this subject.

### Pre-declared direct exchanges

AMQP 0.9.1 brokers must implement a direct exchange type and

pre-declare two instances:

* `amq.direct`

* *""* exchange known as *default exchange* (unnamed, referred to as an empty string by many clients including Bunny)

Applications can rely on those exchanges always being available to

them. Each vhost has separate instances of those exchanges, they are

*not shared across vhosts* for obvious reasons.

### Default exchange

The default exchange is a direct exchange with no name (Bunny refers

to it using an empty string) pre-declared by the broker. It has one

special property that makes it very useful for smaller applications,

namely that *every queue is automatically bound to it with a routing

key which is the same as the queue name*.

For example, when you declare a queue with the name of

"search.indexing.online", RabbitMQ will bind it to the default

exchange using "search.indexing.online" as the routing key. Therefore

a message published to the default exchange with routing key =

"search.indexing.online" will be routed to the queue

"search.indexing.online". In other words, the default exchange makes

it *seem like it is possible to deliver messages directly to queues*,

even though that is not technically what is happening.

The default exchange is used by the "Hello, World" example:

``` ruby

#!/usr/bin/env ruby

# encoding: utf-8

require "rubygems"

require "bunny"

conn = Bunny.new

conn.start

ch = conn.create_channel

q = ch.queue("bunny.examples.hello_world", :auto_delete => true)

q.subscribe do |delivery_info, properties, payload|

puts "Received #{payload}"

end

q.publish("Hello!", :routing_key => q.name)

sleep 1.0

conn.close

```

### Direct Exchange Use Cases

Direct exchanges can be used in a wide variety of cases:

* Direct (near real-time) messages to individual players in an MMO game

* Delivering notifications to specific geographic locations (for example, points of sale)

* Distributing tasks between multiple instances of the same application all having the same function, for example, image processors

* Passing data between workflow steps, each having an identifier (also consider using headers exchange)

* Delivering notifications to individual software services in the network

## Topic Exchanges

### How Topic Exchanges Route Messages

Topic exchanges route messages to one or many queues based on matching

between a message routing key and the pattern that was used to bind a

queue to an exchange. The topic exchange type is often used to

implement various [publish/subscribe

pattern](http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Publish/subscribe) variations.

Topic exchanges are commonly used for the [multicast

routing](http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Multicast) of messages.

Topic exchanges can be used for [broadcast

routing](http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Broadcasting_%28computing%29),

but fanout exchanges are usually more efficient for this use case.

### Topic Exchange Routing Example

Two classic examples of topic-based routing are stock price updates

and location-specific data (for instance, weather

broadcasts). Consumers indicate which topics they are interested in

(think of it like subscribing to a feed for an individual tag of your

favourite blog as opposed to the full feed). The routing is enabled by

specifying a *routing pattern* to the `Bunny::Queue#bind` method, for

example:

``` ruby

x = ch.topic("weather", :auto_delete => true)

q = ch.queue("americas.south", :auto_delete => true).bind(x, :routing_key => "americas.south.#")

q.subscribe do |delivery_info, properties, payload|

puts "An update for South America: #{payload}, routing key is #{delivery_info.routing_key}"

end

```

In the example above we bind a queue with the name of "americas.south" to the topic exchange declared earlier using the `Bunny::Queue#bind` method. This means that

only messages with a routing key matching "americas.south.#" will be routed to the "americas.south" queue.

A routing pattern consists of several words separated by dots, in a

similar way to URI path segments being joined by slash. A few of

examples:

* asia.southeast.thailand.bangkok

* sports.basketball

* usa.nasdaq.aapl

* tasks.search.indexing.accounts

The following routing keys match the "americas.south.#" pattern:

* americas.south

* americas.south.*brazil*

* americas.south.*brazil.saopaulo*

* americas.south.*chile.santiago*

In other words, the "#" part of the pattern matches 0 or more words.

For the pattern "americas.south.*", some matching routing keys are:

* americas.south.*brazil*

* americas.south.*chile*

* americas.south.*peru*

but not

* americas.south

* americas.south.chile.santiago

As you can see, the "*" part of the pattern matches 1 word only.

Full example:

``` ruby

#!/usr/bin/env ruby

# encoding: utf-8

require "rubygems"

require "bunny"

connection = Bunny.new

connection.start

channel = connection.create_channel

# topic exchange name can be any string

exchange = channel.topic("weather", :auto_delete => true)

# Subscribers.

channel.queue("americas.north").bind(exchange, :routing_key => "americas.north.#").subscribe do |delivery_info, properties, payload|

puts "An update for North America: #{payload}, routing key is #{delivery_info.routing_key}"

end

channel.queue("americas.south").bind(exchange, :routing_key => "americas.south.#").subscribe do |delivery_info, properties, payload|

puts "An update for South America: #{payload}, routing key is #{delivery_info.routing_key}"

end

channel.queue("us.california").bind(exchange, :routing_key => "americas.north.us.ca.*").subscribe do |delivery_info, properties, payload|

puts "An update for US/California: #{payload}, routing key is #{delivery_info.routing_key}"

end

channel.queue("us.tx.austin").bind(exchange, :routing_key => "#.tx.austin").subscribe do |delivery_info, properties, payload|

puts "An update for Austin, TX: #{payload}, routing key is #{delivery_info.routing_key}"

end

channel.queue("it.rome").bind(exchange, :routing_key => "europe.italy.rome").subscribe do |delivery_info, properties, payload|

puts "An update for Rome, Italy: #{payload}, routing key is #{delivery_info.routing_key}"

end

channel.queue("asia.hk").bind(exchange, :routing_key => "asia.southeast.hk.#").subscribe do |delivery_info, properties, payload|

puts "An update for Hong Kong: #{payload}, routing key is #{delivery_info.routing_key}"

end

exchange.publish("San Diego update", :routing_key => "americas.north.us.ca.sandiego").

publish("Berkeley update", :routing_key => "americas.north.us.ca.berkeley").

publish("San Francisco update", :routing_key => "americas.north.us.ca.sanfrancisco").

publish("New York update", :routing_key => "americas.north.us.ny.newyork").

publish("São Paulo update", :routing_key => "americas.south.brazil.saopaulo").

publish("Hong Kong update", :routing_key => "asia.southeast.hk.hongkong").

publish("Kyoto update", :routing_key => "asia.southeast.japan.kyoto").

publish("Shanghai update", :routing_key => "asia.southeast.prc.shanghai").

publish("Rome update", :routing_key => "europe.italy.roma").

publish("Paris update", :routing_key => "europe.france.paris")

sleep 1.0

connection.close

```

### Topic Exchange Use Cases

Topic exchanges have a very broad set of use cases. Whenever a problem

involves multiple consumers/applications that selectively choose which

type of messages they want to receive, the use of topic exchanges

should be considered. To name a few examples:

* Distributing data relevant to specific geographic location, for example, points of sale

* Background task processing done by multiple workers, each capable of handling specific set of tasks

* Stocks price updates (and updates on other kinds of financial data)

* News updates that involve categorization or tagging (for example, only for a particular sport or team)

* Orchestration of services of different kinds in the cloud

* Distributed architecture/OS-specific software builds or packaging where each builder can handle only one architecture or OS

## Declaring/Instantiating Exchanges

With Bunny, exchanges can be declared in two ways: by instantiating

`Bunny::Exchange` or by using a number of convenience methods on

`Bunny::Channel`:

* `Bunny::Channel#default_exchange`

* `Bunny::Channel#direct`

* `Bunny::Channel#topic`

* `Bunny::Channel#fanout`

* `Bunny::Channel#headers`

The previous sections on specific exchange types (direct, fanout,

headers, etc.) provide plenty of examples of how these methods can be

used.

## Checking if an Exchange Exists

Sometimes it's convenient to check if an exchange exists. To do so, at the protocol

level you use `exchange.declare` with `passive` seto to `true`. In response

RabbitMQ responds with a channel exception if the exchange does not exist.

Bunny provides a convenience method, `Bunny::Session#exchange_exists?`, to do this:

``` ruby

conn = Bunny.new

conn.start

conn.exchange_exists?("logs")

```

## Publishing messages

To publish a message to an exchange, use `Bunny::Exchange#publish`:

``` ruby

x.publish("some data")

```

The method accepts message body and a number of message and delivery metadata options. Routing key can be blank (`""`) but never `nil`.

The body needs to be a string. The message payload is completely opaque to the library and is not modified by Bunny or RabbitMQ in any way.

### Data serialization

You are encouraged to take care of data serialization before publishing (i.e. by using JSON, Thrift, Protocol Buffers or some other serialization library).

Note that because AMQP is a binary protocol, text formats like JSON largely lose their advantage of being easy to inspect as data travels across the network,

so if bandwidth efficiency is important, consider using [MessagePack](http://msgpack.org/) or [Protocol Buffers](http://code.google.com/p/protobuf/).

A few popular options for data serialization are:

* JSON: [json gem](https://rubygems.org/gems/json) (part of standard Ruby library on Ruby 1.9) or [yajl-ruby](https://rubygems.org/gems/yajl-ruby) (Ruby bindings to YAJL)

* BSON: [bson gem](https://rubygems.org/gems/bson) for JRuby (implemented as a Java extension) or [bson_ext](https://rubygems.org/bson_ext) for C-based Rubies

* [Message Pack](http://msgpack.org) has Ruby bindings and provides a Java implementation for JRuby

* XML: [Nokogiri](https://nokogiri.org) is a swiss army knife for XML processing with Ruby, built on top of libxml2

* Protocol Buffers: [beefcake](https://github.com/bmizerany/beefcake)

### Message metadata

RabbitMQ messages have various metadata attributes that can be set

when a message is published. Some of the attributes are well-known and

mentioned in the AMQP 0.9.1 specification, others are specific to a

particular application. Well-known attributes are listed here as

options that `Bunny::Exchange#publish` takes:

* `:persistent`

* `:mandatory`

* `:timestamp`

* `:expiration`

* `:type`

* `:reply_to`

* `:content_type`

* `:content_encoding`

* `:correlation_id`

* `:priority`

* `:message_id`

* `:user_id`

* `:app_id`

All other attributes can be added to a *headers table* (in Ruby, a

hash) that `Bunny::Exchange#publish` accepts as the `:headers` option.

An example:

``` ruby

# or Process.clock_gettime(Process::CLOCK_MONOTONIC) if using a monotonic clock is important

now = Time.now

x.publish("hello",

:routing_key => queue_name,

:app_id => "bunny.example",

:priority => 8,

:type => "kinda.checkin",

# headers table keys can be anything

:headers => {

:coordinates => {

:latitude => 59.35,

:longitude => 18.066667

},

:time => now,

:participants => 11,

:venue => "Stockholm",

:true_field => true,

:false_field => false,

:nil_field => nil,

:ary_field => ["one", 2.0, 3, [{"abc" => 123}]]

},

:timestamp => now.to_i,

:reply_to => "a.sender",

:correlation_id => "r-1",

:message_id => "m-1")

```

<dl>

<dt>:routing_key</dt>

<dd>Used for routing messages depending on the exchange type and configuration.</dd>

<dt>:persistent</dt>

<dd>When set to true, RabbitMQ will persist message to disk.</dd>

<dt>:mandatory</dt>

<dd>

This flag tells the server how to react if the message cannot be routed to a queue. If this flag is set to true, the server will return an unroutable message

to the producer with a `basic.return` AMQP method. If this flag is set to false, the server silently drops the message.

</dd>

<dt>:content_type</dt>

<dd>MIME content type of message payload. Has the same purpose/semantics as HTTP Content-Type header.</dd>

<dt>:content_encoding</dt>

<dd>MIME content encoding of message payload. Has the same purpose/semantics as HTTP Content-Encoding header.</dd>

<dt>:priority</dt>

<dd>Message priority, from 0 to 9.</dd>

<dt>:message_id</dt>

<dd>

Message identifier as a string. If applications need to identify messages, it is recommended that they use this attribute instead of putting it

into the message payload.

</dd>

<dt>:reply_to</dt>

<dd>

Commonly used to name a reply queue (or any other identifier that helps a consumer application to direct its response).

Applications are encouraged to use this attribute instead of putting this information into the message payload.

</dd>

<dt>:correlation_id</dt>

<dd>

ID of the message that this message is a reply to. Applications are encouraged to use this attribute instead of putting this information

into the message payload.

</dd>

<dt>:type</dt>

<dd>Message type as a string. Recommended to be used by applications instead of including this information into the message payload.</dd>

<dt>:user_id</dt>

<dd>

Sender's identifier. Note that RabbitMQ will check that the <a href="http://www.rabbitmq.com/validated-user-id.html">value of this attribute is the same as username AMQP connection was authenticated with</a>, it SHOULD NOT be used to transfer, for example, other application user ids or be used as a basis for some kind of Single Sign-On solution.

</dd>

<dt>:app_id</dt>

<dd>Application identifier string, for example, "eventoverse" or "webcrawler"</dd>

<dt>:timestamp</dt>

<dd>Timestamp of the moment when message was sent, in seconds since the Epoch</dd>

<dt>:expiration</dt>

<dd>Message expiration specification as a string</dd>

<dt>:arguments</dt>

<dd>A map of any additional attributes that the application needs. Nested hashes are supported. Keys must be strings.</dd>

</dl>

It is recommended that application authors use well-known message

attributes when applicable instead of relying on custom headers or

placing information in the message body. For example, if your

application messages have priority, publishing timestamp, type and

content type, you should use the respective AMQP message attributes

instead of reinventing the wheel.

### Validated User ID

In some scenarios it is useful for consumers to be able to know the

identity of the user who published a message. RabbitMQ implements a

feature known as [validated User

ID](http://www.rabbitmq.com/extensions.html#validated-user-id). If

this property is set by a publisher, its value must be the same as the

name of the user used to open the connection. If the user-id property

is not set, the publisher's identity is not validated and remains

private.

### Publishing Callbacks and Reliable Delivery in Distributed Environments

A commonly asked question about RabbitMQ clients is "how to execute a

piece of code after a message is received".

Message publishing with Bunny happens in several steps:

* `Bunny::Exchange#publish` takes a payload and various metadata attributes

* Resulting payload is staged for writing

* On the next event loop tick, data is transferred to the OS kernel using one of the underlying NIO APIs

* OS kernel buffers data before sending it

* Network driver may also employ buffering

<div class="alert alert-error"> As you can see, "when data is sent" is

a complicated issue and while methods to flush buffers exist, flushing

buffers does not guarantee that the data was received by the broker

because it might have crashed while data was travelling down the wire.

The only way to reliably know whether data was received by the broker or a peer application is to use message acknowledgements. This is how TCP works and this

approach is proven to work at the enormous scale of the modern Internet. AMQP 0.9.1 fully embraces this fact and Bunny follows.

</div>

In cases when you cannot afford to lose a single message, AMQP 0.9.1

applications can use one (or a combination of) the following protocol

features:

* Publisher confirms (a RabbitMQ-specific extension to AMQP 0.9.1)

* Publishing messages as mandatory

* Transactions (these introduce noticeable overhead and have a relatively narrow set of use cases)

A more detailed overview of the pros and cons of each option can be

found in a [blog post that introduces Publisher Confirms

extension](http://bit.ly/rabbitmq-publisher-confirms) by the RabbitMQ

team. The next sections of this guide will describe how the features

above can be used with Bunny.

### Publishing messages as mandatory

When publishing messages, it is possible to use the `:mandatory`

option to publish a message as "mandatory". When a mandatory message

cannot be *routed* to any queue (for example, there are no bindings or

none of the bindings match), the message is returned to the producer.

The following code example demonstrates a message that is published as

mandatory but cannot be routed (no bindings) and thus is returned back

to the producer:

``` ruby

#!/usr/bin/env ruby

# encoding: utf-8

require "rubygems"

require "bunny"

puts "=> Publishing messages as mandatory"

puts

conn = Bunny.new

conn.start

ch = conn.create_channel

x = ch.default_exchange

x.on_return do |return_info, properties, content|

puts "Got a returned message: #{content}"

end

q = ch.queue("", :exclusive => true)

q.subscribe do |delivery_info, properties, content|

puts "Consumed a message: #{content}"

end

x.publish("This will NOT be returned", :mandatory => true, :routing_key => q.name)

x.publish("This will be returned", :mandatory => true, :routing_key => "akjhdfkjsh#{rand}")

sleep 0.5

puts "Disconnecting..."

conn.close

```

### Returned messages

When a message is returned, the application that produced it can

handle that message in different ways:

* Store it for later redelivery in a persistent store

* Publish it to a different destination

* Log the event and discard the message

Returned messages contain information about the exchange they were

published to. Bunny associates returned message callbacks with

consumers. To handle returned messages, use

`Bunny::Exchange#on_return`:

``` ruby

#!/usr/bin/env ruby

# encoding: utf-8

require "rubygems"

require "bunny"

puts "=> Publishing messages as mandatory"

puts

conn = Bunny.new

conn.start

ch = conn.create_channel

x = ch.default_exchange

x.on_return do |return_info, properties, content|

puts "Got a returned message: #{content}"

end

q = ch.queue("", :exclusive => true)

q.subscribe do |delivery_info, properties, content|

puts "Consumed a message: #{content}"

end

x.publish("This will NOT be returned", :mandatory => true, :routing_key => q.name)

x.publish("This will be returned", :mandatory => true, :routing_key => "akjhdfkjsh#{rand}")

sleep 0.5

puts "Disconnecting..."

conn.close

```

A returned message handler has access to AMQP method (`basic.return`)

information, message metadata and payload (as a byte array). The

metadata and message body are returned without modifications so that

the application can store the message for later redelivery.

### Publishing Persistent Messages

Messages potentially spend some time in the queues to which they were

routed before they are consumed. During this period of time, the

broker may crash or experience a restart. To survive it, messages

must be persisted to disk. This has a negative effect on performance,

especially with network attached storage like NAS devices and Amazon

EBS. AMQP 0.9.1 lets applications trade off performance for

durability, or vice versa, on a message-by-message basis.

To publish a persistent message, use the `:persistent` option that

`Bunny::Exchange#publish` accepts:

``` ruby

x.publish(data, :persistent => true)

```

**Note** that in order to survive a broker crash, the messages MUST be persistent and the queue that they were routed to MUST be durable.

[Durability and Message Persistence](/articles/durability.html) provides more information on the subject.

### Message Priority

Starting with RabbitMQ 3.5, queues can be [instructed to support

message priorities](https://www.rabbitmq.com/priority.html).

To specify a priority on a message, pass the `:priority` key to

`Bunny::Exchange#publish`. Note that priority queues have certain

[limitations listed in the RabbitMQ documentation](https://www.rabbitmq.com/priority.html).

### Publishing In Multi-threaded Environments

<div class="alert alert-error">

When using Bunny in multi-threaded

environments, the rule of thumb is: avoid sharing channels across

threads.

</div>

In other words, publishers in your application that publish from

separate threads should use their own channels. The same is a good

idea for consumers.

## Headers exchanges

Now that message attributes and publishing have been introduced, it is

time to take a look at one more core exchange type in AMQP 0.9.1. It

is called the *headers exchange type* and is quite powerful.

### How headers exchanges route messages

#### An Example Problem Definition

The best way to explain headers-based routing is with an

example. Imagine a distributed [continuous

integration](http://martinfowler.com/articles/continuousIntegration.html)

system that distributes builds across multiple machines with different

hardware architectures (x86, IA-64, AMD64, ARM family and so on) and

operating systems. It strives to provide a way for a community to

contribute machines to run tests on and a nice build matrix like [the

one WebKit uses](http://build.webkit.org/waterfall?category=core).

One key problem such systems face is build distribution. It would be

nice if a messaging broker could figure out which machine has which

OS, architecture or combination of the two and route build request

messages accordingly.

A headers exchange is designed to help in situations like this by

routing on multiple attributes that are more easily expressed as

message metadata attributes (headers) rather than a routing key

string.

#### Routing on Multiple Message Attributes

Headers exchanges route messages based on message header

matching. Headers exchanges ignore the routing key attribute. Instead,

the attributes used for routing are taken from the "headers"

attribute. When a queue is bound to a headers exchange, the

`:arguments` attribute is used to define matching rules:

``` ruby

q = ch.queue("hosts.ip-172-37-11-56")

x = ch.headers("requests")

q.bind(x, :arguments => {"os" => "linux"})

```

When matching on one header, a message is considered matching if the

value of the header equals the value specified upon binding. An

example that demonstrates headers routing:

``` ruby

#!/usr/bin/env ruby

# encoding: utf-8

require "rubygems"

require "bunny"

puts "=> Headers exchange routing"

puts

conn = Bunny.new

conn.start

ch = conn.create_channel

x = ch.headers("headers")

q1 = ch.queue("", :exclusive => true).bind(x, :arguments => {"os" => "linux", "cores" => 8, "x-match" => "all"})

q2 = ch.queue("", :exclusive => true).bind(x, :arguments => {"os" => "osx", "cores" => 4, "x-match" => "any"})

q1.subscribe do |delivery_info, properties, content|

puts "#{q1.name} received #{content}"

end

q2.subscribe do |delivery_info, properties, content|

puts "#{q2.name} received #{content}"

end

x.publish("8 cores/Linux", :headers => {"os" => "linux", "cores" => 8})

x.publish("8 cores/OS X", :headers => {"os" => "osx", "cores" => 8})

x.publish("4 cores/Linux", :headers => {"os" => "linux", "cores" => 4})

sleep 0.5

conn.close

```

When executed, it outputs

```

=> Headers exchange routing

amq.gen-xhIzykDAjfcC4orMsi0O6Q received 8 cores/Linux

amq.gen-6O1oKjVd8QbKr7zyy7ssbg received 8 cores/OS X

amq.gen-6O1oKjVd8QbKr7zyy7ssbg received 4 cores/Linux

```

#### Matching All vs Matching One

It is possible to bind a queue to a headers exchange using more than

one header for matching. In this case, the broker needs one more piece

of information from the application developer, namely, should it

consider messages with any of the headers matching, or all of them?

This is what the "x-match" binding argument is for.

When the `"x-match"` argument is set to `"any"`, just one matching

header value is sufficient. So in the example above, any message with

a "cores" header value equal to 8 will be considered matching.

### Declaring a Headers Exchange

There are two ways to declare a headers exchange, either instantiate

`Bunny::Exchange` directly:

``` ruby

x = Bunny::Exchange.new(ch, :headers, "matching")

```

Or use the `Bunny::Channel#headers` method:

``` ruby

x = ch.headers("matching")

```

### Headers Exchange Routing

When there is just one queue bound to a headers exchange, messages are

routed to it if any or all of the message headers match those

specified upon binding. Whether it is "any header" or "all of them"

depends on the `"x-match"` header value. In the case of multiple

queues, a headers exchange will deliver a copy of a message to each

queue, just like direct exchanges do. Distribution rules between

consumers on a particular queue are the same as for a direct exchange.

### Headers Exchange Use Cases

Headers exchanges can be looked upon as "direct exchanges on steroids"

and because they route based on header values, they can be used as

direct exchanges where the routing key does not have to be a string;

it could be an integer or a hash (dictionary) for example.

Some specific use cases:

* Transfer of work between stages in a multi-step workflow ([routing slip pattern](http://eaipatterns.com/RoutingTable.html))

* Distributed build/continuous integration systems can distribute builds based on multiple parameters (OS, CPU architecture, availability of a particular package).

### Pre-declared Headers Exchanges

RabbitMQ implements a headers exchange type and pre-declares one

instance with the name of `"amq.match"`. RabbitMQ also pre-declares

one instance with the name of `"amq.headers"`. Applications can rely

on those exchanges always being available to them. Each vhost has a

separate instance of those exchanges and they are *not shared across

vhosts* for obvious reasons.

## Custom Exchange Types

### consistent-hash

The [consistent hashing AMQP exchange

type](https://github.com/rabbitmq/rabbitmq-consistent-hash-exchange)

is a custom exchange type developed as a RabbitMQ plugin. It uses

[consistent

hashing](http://michaelnielsen.org/blog/consistent-hashing/) to route

messages to queues. This helps distribute messages between queues more

or less evenly.

A quote from the project README:

> In various scenarios, you may wish to ensure that messages sent to an exchange are consistently and equally distributed across a number of different queues based on

> the routing key of the message. You could arrange for this to occur yourself by using a direct or topic exchange, binding queues to that exchange and then publishing

> messages to that exchange that match the various binding keys.

>

> However, arranging things this way can be problematic:

>

> It is difficult to ensure that all queues bound to the exchange will receive a (roughly) equal number of messages without baking in to the publishers quite a lot of

> knowledge about the number of queues and their bindings.

>

> If the number of queues changes, it is not easy to ensure that the new topology still distributes messages between the different queues evenly.

>

> Consistent Hashing is a hashing technique whereby each bucket appears at multiple points throughout the hash space, and the bucket selected is the nearest

> higher (or lower, it doesn't matter, provided it's consistent) bucket to the computed hash (and the hash space wraps around). The effect of this is that when a new

> bucket is added or an existing bucket removed, only a very few hashes change which bucket they are routed to.

>

> In the case of Consistent Hashing as an exchange type, the hash is calculated from the hash of the routing key of each message received. Thus messages that have

> the same routing key will have the same hash computed, and thus will be routed to the same queue, assuming no bindings have changed.

### x-random

The [x-random AMQP exchange

type](https://github.com/jbrisbin/random-exchange) is a custom

exchange type developed as a RabbitMQ plugin by Jon Brisbin. A quote

from the project README:

> It is basically a direct exchange, with the exception that, instead of each consumer bound to that exchange with the same routing key

> getting a copy of the message, the exchange type randomly selects a queue to route to.

This plugin is licensed under [Mozilla Public License

1.1](http://www.mozilla.org/MPL/MPL-1.1.html), same as RabbitMQ.

## Using the Publisher Confirms Extension

Please refer to [RabbitMQ Extensions guide](/articles/extensions.html)

### Message Acknowledgements and Their Relationship to Transactions and Publisher Confirms

Consumer applications (applications that receive and process messages)

may occasionally fail to process individual messages, or might just

crash. Additionally, network issues might be experienced. This raises

a question - "when should the RabbitMQ remove messages from queues?"

This topic is covered in depth in the [Queues

guide](/articles/queues.html), including prefetching and examples.

In this guide, we will only mention how message acknowledgements are

related to AMQP transactions and the Publisher Confirms extension. Let

us consider a publisher application (P) that communications with a

consumer (C) using AMQP 0.9.1. Their communication can be graphically

represented like this:

<pre>

----- ----- -----

| | S1 | | S2 | |

| P | ====> | B | ====> | C |

| | | | | |

----- ----- -----

</pre>

We have two network segments, S1 and S2. Each of them may fail. A publisher (P) is concerned with making sure that messages cross S1, while the broker (B) and consumer (C) are concerned

with ensuring that messages cross S2 and are only removed from the queue when they are processed successfully.

Message acknowledgements cover reliable delivery over S2 as well as successful processing. For S1, P has to use transactions (a heavyweight solution) or the more

lightweight Publisher Confirms, a RabbitMQ-specific extension.

## Binding Queues to Exchanges

Queues are bound to exchanges using `Bunny::Queue#bind`. This topic is

described in detail in the [Queues and Consumers

guide](/articles/queues.html).

## Unbinding Queues from Exchanges

Queues are unbound from exchanges using `Bunny::Queue#unbind`. This

topic is described in detail in the [Queues and Consumers

guide](/articles/queues.html).

## Deleting Exchanges

### Explicitly Deleting an Exchange

Exchanges are deleted using the `Bunny::Exchange#delete`:

``` ruby

x = ch.topic("groups.013c6a65a1de9b15658446c6570ec39ff615ba15")

x.delete

```

### Auto-deleted exchanges

Exchanges can be *auto-deleted*. To declare an exchange as

auto-deleted, use the `:auto_delete` option on declaration:

``` ruby

ch.topic("groups.013c6a65a1de9b15658446c6570ec39ff615ba15", :auto_delete => true)

```

An auto-deleted exchange is removed when the last queue bound to it

is unbound.

## Exchange durability vs Message durability

See [Durability guide](/articles/durability.html)

## Wrapping Up

Publishers publish messages to exchanges. Messages are then routed to queues according to rules called bindings

that applications define. There are 4 built-in exchange types in RabbitMQ and it is possible to create custom

types.

Messages have a set of standard properties (e.g. type, content type) and can carry an arbitrary map

of headers.

Most functions related to exchanges and publishing are found in two Bunny classes:

* `Bunny::Exchange`

* `Bunny::Channel`

## What to Read Next

The documentation is organized as [a number of

guides](/articles/guides.html), covering various topics.

We recommend that you read the following guides first, if possible, in

this order:

* [Bindings](/articles/bindings.html)

* [RabbitMQ Extensions to AMQP 0.9.1](/articles/extensions.html)

* [Durability and Related Matters](/articles/durability.html)

* [Error Handling and Recovery](/articles/error_handling.html)

* [Concurrency Considerations](/articles/concurrency.html)

* [Troubleshooting](/articles/troubleshooting.html)

* [Using TLS (SSL) Connections](/articles/tls.html)

## Tell Us What You Think!

Please take a moment to tell us what you think about this guide [on

Twitter](http://twitter.com/rubyamqp) or the [Bunny mailing

list](https://groups.google.com/forum/#!forum/ruby-amqp)

Let us know what was unclear or what has not been covered. Maybe you

do not like the guide style or grammar or discover spelling

mistakes. Reader feedback is key to making the documentation better.

|